Biden And The Mirage Of American Democracy

Americans should tolerate no president invoking “the will of the people” to sanctify his crimes.

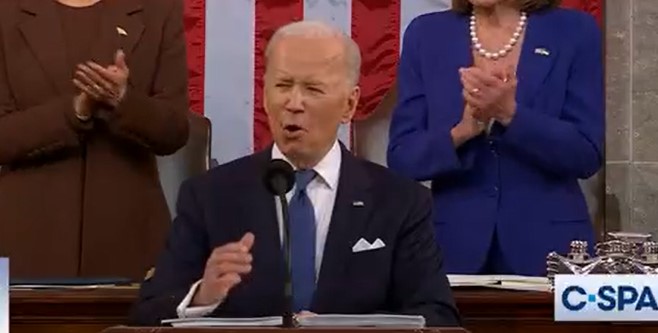

Since late 2020, President Joe Biden has invoked “the will of the people” dozens of times to sanctify his power, including arbitrary decrees that were illegal or unconstitutional. Biden’s invocations did not prevent his re-election campaign from being terminated behind closed doors on Sunday by Democratic Party donors and leaders. Though Biden is being shoved off stage, the “will of the people” will continue to be invoked to raze limits on presidential power and trample the Bill of Rights.

Biden’s rhetorical machinations ignore the lessons from ideological clashes in the 1700s between Americans and British over the doctrine of representation. Biden, like most modern American presidents, reflects a radical redefinition of democracy stemming from Jean-Jacques Rousseau—a change that helped turn the French Revolution into a bloodbath.

Conflicts between the American colonists and British rulers reached a fever pitch in the 1760s. The Sugar Act of 1764 resulted in British officials confiscating hundreds of American ships, based on mere allegations that the shipowners or captains were involved in smuggling; Americans were obliged, in order to retain their ships, to somehow prove that they had never been involved in smuggling—a near-impossible burden. The Stamp Act of 1765 obliged Americans to purchase British stamps to be used on all legal papers, newspapers, cards, dice, advertisements, and even on academic degrees. After violent protests throughout the colonies, the Parliament rescinded the Stamp Act but passed the Declaratory Act, which announced that Parliament “had, hath, and of right ought to have, full power and authority to make laws and statutes of sufficient force and validity to bind the colonies and people of America, subjects of the crown of Great Britain, in all cases whatsoever.” The Declaratory Act meant that Parliament could never do an injustice to the Americans, since Parliament had the right to use and abuse the colonists as it chose.

Many American colonists believed that, for them, British representative government was a fraud. The “Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms,” issued by the Second Continental Congress on July 6, 1775, a few weeks after the Battle of Bunker Hill, highlighted the crimes of the British Parliament. (The Declaration of Independence, issued almost a year later, concentrated on King George III as the personification of British abuses.) The Declaration, written by John Dickinson and Thomas Jefferson, complained that “the legislature of Great Britain, stimulated by an inordinate passion for power…attempted to effect their cruel and impolitic purpose of enslaving these colonies by violence.” The Continental Congress demanded to know, “What is to defend us against so enormous, so unlimited a power? Not a single man of those who assume it, is chosen by us; or is subject to our control or influence.”

Americans and British profoundly disagreed on the source of their freedom. Many British believed that freedom depended on vesting unlimited power in the Parliament, since they believed the only threat to their freedom came from the king and his lackeys. Sir William Meredith praised the British constitution in 1769 because it was the privilege of the Englishman alone “to choose those delegates to whose Charge is committed the Disposal of his Property, his Liberty, his Life.” In 1768, the Speaker of the House of Commons announced, “The freedom of this house is the freedom of this country.” As Professor John Phillip Reid observed in 1988, “This new or ‘radical’ constitutional theory was a departure from the British tradition of defining liberty without having its preservation depend on specific institutions, presaging the nineteenth century and the general British acceptance of what in the eighteenth century had been constitutional heresy—that liberty and arbitrary power are not incompatible, if the power that is arbitrary is ‘representative.’”

Because Parliament supposedly automatically had the concerns of the entire British Empire at heart, Americans were told they had “virtual representation,” regardless of the fact that they could not vote for any member of Parliament. The British claimed that the Americans were free because they were permitted to petition members of Parliament with their grievances, even though their petitions were routinely not accepted or read.

“Slavery by Parliament” was the phrase commonly used to denounce British legislative power grabs. Americans believed that the power of representatives was strictly limited by the rights of the governed, a doctrine later enshrined in the Bill of Rights. Pamphleteer John Cartwright in 1776 derided “that poor consolatory word, representation, with the mere sound of which we have so long contented ourselves.” James Otis, a heroic Massachusetts lawyer, asked, “Will any man’s calling himself my agent, representative, or trustee make him so in fact? At this rate a House of Commons in one of the colonies have but to conceive an opinion that they represent all the common people of Great Britain, and…they would in fact represent them.”

At the same time that the Americans were fighting a revolution against the fraud of representation, continental Europe was swooning for doctrines that opened an intellectual Pandora’s Box. From the 1600s onwards, the abuses of monarchs made representative government increasingly attractive. Unfortunately, at a time when most continental Europeans had scant political experience, the doctrines of Rousseau swept the intellectual field. Rousseau unleashed the genie of absolute power in the name of popular sovereignty.

Rousseau’s 1762 book, Social Contract, merged contemporary romanticism and mysticism with eighteenth-century political thought. Rousseau thereby gave people an engraved invitation to delude themselves about the nature of majorities, government, and freedom. Rousseau asserted that representative governments are based on the “general will,” which, naturally, could be different from the conscious will of the people themselves:

“It follows from what has gone before that the general will is always right and tends to the public advantage; but it does not follow that the deliberations of the people are always equally correct. Our will is always for our own good, but we do not always see what that is; the people is never corrupted, but it is often deceived, and on such occasions only does it seem to will what is bad.”

Regrettably, Rousseau provided few hints on how either rulers or ruled could recognize the general will. The fact that people opposed surrendering more power to government merely proved that people did not know their own will.

Rousseau waved a philosophic magic wand and pretended that his doctrine of the general will had solved all the problems of representative government. As historian William Dunning noted in 1920, “The common interest and the general will assumed, through [Rousseau’s] manipulation, a greater definiteness and importance than philosophy had hitherto ascribed to them. They became the central features of almost every theory of the State.” Rousseau’s doctrine of the general will became the invocation of rulers seeking unlimited power; Hitler’s Volk was the Teutonic rendition of Rousseau’s doctrine. J. L. Talmon, author of The Origins of Totalitarian Democracy, concluded that Rousseau “was unaware that total and highly emotional absorption in the collective political endeavor is calculated to kill all privacy…and the extension of the scope of politics to all spheres of human interest and endeavor…was the shortest way to totalitarianism.”

In contrast to Rousseau, the Founding Fathers were keenly aware of the potential abuses of popular government. The American Revolution was based on cynicism about the fraud of representation in the British Parliament; the French Revolution, following Rousseau’s doctrine, was based on the delusion that the people are infallible and that democratic government automatically pursues the common good. One revolution was based on distrust of government, the other on messianic expectations from a change in form of a government. While John Adams naively declared in 1775 that “a democratical despotism is a contradiction in terms,” few Americans held that belief by the mid-1780s. Judge Alexander Hanson declared in 1784, “The acts of almost every legislature have uniformly tended to disgust its citizens and to annihilate its credit.” One commentator in the 1780s, noting the early dashed hopes of democratic governments, declared that the usurpation of “40 tyrants at our doors, exceeds that of one at 3,000 miles.” Gordon Wood, author of The Creation of the American Republic, noted, “Throughout the years of the war and after, Americans in almost all the states mounted increasing attacks on the tendencies of the American representational system.” James Madison wrote in the Federalist Papers, “Complaints are everywhere heard…that [government] measures are too often decided, not according to the rules of justice and the rights of the minor party, but by the superior force of an interested and overbearing majority.”

Unfortunately, the doctrines of Rousseau have had far more influence on subsequent thinking about democracy than the insights of Madison and other Founding Fathers. Throughout American history, more attention has been paid to the rhetoric and ideals of democracy than to its substance. Lysander Spooner, a Massachusetts abolitionist, ridiculed President Abraham Lincoln’s claim that the Civil War was fought to preserve a “government by consent.” Spooner observed, “The only idea…ever manifested as to what is a government of consent, is this—that it is one to which everybody must consent, or be shot.”

“Consent or be shot” is still the prevailing notion of democracy in Washington. (Ask the Waco survivors.) It doesn’t help that phalanxes of pro-government pundits have less familiarity with philosophy than your average big city bartender. Intellectual curiosity was seemingly banned inside the Beltway decades ago.

Unfortunately, Biden’s demise is spurring few people to question the fundamentals of a system that exploited a deluded hack to sanctify nearly absolute power. Chances are slim that either Republicans or Democrats will honor the standard that the Supreme Court trumpeted in 1943: “The very purpose of a Bill of Rights was to withdraw certain subjects…beyond the reach of majorities and officials.” Instead, America can look forward to another hundred days of demagoguery and fearmongering, after which the winner will again claim to incarnate “the will of the people.”

An earlier version of this piece was posted by the Libertarian Institute.

Comments are closed.