On the hundredth anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution, here’s an essay I wrote on why private property rights are the foundation of individual liberty. Where private property rights are nullified, people live at the mercy of bureaucrats and politicians. This spinoff from my 1999 book Freedom in Chains, was published by the Freeman in 2000 by my fav editor, Sheldon Richman.

Freeman, September 2000

Property and Liberty

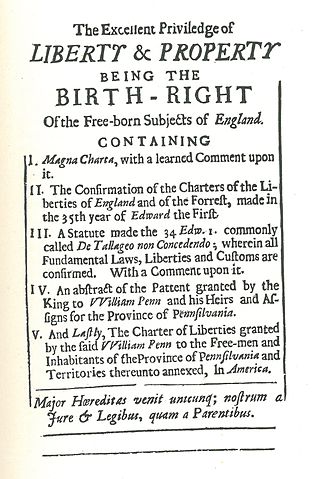

Property is “the guardian of all other rights,” as Arthur Lee of Virginia wrote in 1775.[1] The Supreme Court declared in 1897: “In a free government almost all other rights would become worthless if the government possessed power over the private fortune of every citizen.”[2] Unfortunately, legislators, judges, and political philosophers in the twentieth century have perennially disparaged property’s value to freedom.

Without private property, there is no escape from state power. Property rights are the border guards around an individual’s life that deter political invasions. Those who disparage property often oppose any meaningful limits on government power. John Dewey, for instance, derided “the sanctity of private property” for providing “freedom from social control.”[3] Socialist regimes despise property because it limits the power of the state to regiment the lives of the people. A 1975 study, The Soviet Image of Utopia, observed, “The closely knit communities of communism will be able to locate the anti-social individual without difficulty because he will not be able to ‘shut the door of his apartment’ and retreat to an area of his life that is ‘strictly private.’”[4] Hungarian economist Janos Kornai observed: “The further elimination of private ownership is taken, the more consistently can full subjection be imposed.”[5]

Yet Oxford professor John Gray asserted in 1990 that “very extensive State intervention in the economy has nowhere resulted in the extinction of basic personal and political liberties.”[6] One wonders which freedoms Bulgarian and Romanian citizens enjoyed under communism that Gray neglects to mention. Perpetual shortages of almost all goods characterized East Bloc economies; politicians and bureaucrats maximized their power and maximized people’s subjugation through discretionary doling out of goods. Shortages created new pretexts to demand further submission: the worse the economic system functioned, the more power government acquired—until the people rose up and destroyed the governments.[7]

The Economy Is Lives

Government cannot control the economy without controlling the lives of everyone who must rely on that economy to earn his sustenance. There is more to life than wealth. But the more wealth government seizes from people, the more likely that government will be able to control all the other good things in life. Once government domineers the economy, it becomes far more difficult to resist the extension of government power further and further into the recesses of each person’s life.

Property rights are not concerned merely with the sanctity of the estates of the rich. The property right that each citizen has in himself is the foundation of a free society. As James Madison observed, “Government is instituted to protect property of every sort; as well that which lies in the various rights of individuals, as that which the term particularly expresses.”[8] The property that each citizen has in his rights is the foundation of his ability to control his own life and strive to shape his own destiny.

Some contemporary liberals argue that government ownership is the ultimate safeguard of freedom. According to Alan Wolfe, “No one would be able to enjoy the negative liberty of walking alone in the wilderness if it were not for the regulatory capacity of government to protect the wilderness against development.”[9] Wolfe implies that if the government did not own much of the nation’s land, private citizens would ravage the landscape from coast to coast. However, private landowners have a better record of safeguarding the environmental quality of their land than does the federal government.[10] The Army Corps of Engineers has destroyed far more of the natural river beauty in this country than has any private malefactor, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s lavish subsidies for “flood insurance” have made possible vast numbers of buildings on ecologically fragile coastlines.[11] Wolfe also implies that no private forest owner would permit anyone else to walk on his land. However, the proliferation of contracts for hunting on private land show that, with a sound incentive system, access to private land can easily be negotiated. Citizens have different values, and many citizens prefer to keep their land in semi-pristine condition. Besides, even if all citizens wanted to sell their land to developers, only a small percentage of such land would be developed—simply because there is no economic rationale for developing much of rural America.

Bulwark of Privacy

The sanctity of private property is the most important bulwark of privacy. University of Chicago law professor Richard Epstein wrote that “private property gives the right to exclude others without the need for any justification. Indeed, it is the ability to act at will and without need for justification within some domain which is the essence of freedom, be it of speech or of property.”[12] Unfortunately, federal law enforcement agents and prosecutors are making private property much less private. In 1984 the Supreme Court ruled in Oliver v. United States—a case involving Kentucky law-enforcement agents who ignored several “No Trespassing” signs, climbed over a fence, tramped a mile and a half onto a person’s land and found marijuana plants—that “open fields do not provide the setting for those intimate activities that the [Fourth] Amendment is intended to shelter from government interference or surveillance.”[13] (The Founding Fathers apparently forgot to include a parenthesis in the original Fourth Amendment specifying that it applied only to “intimate activities.”) And the Court made it clear that it was not referring only to open fields: “A thickly wooded area nonetheless may be an open field as that term is used in construing the Fourth Amendment.”[14] Justice Thurgood Marshall dissented: “Many landowners like to take solitary walks on their property, confident that they will not be confronted in their rambles by strangers or policemen.”[15] Even prior to this ruling, it was easy for law-enforcement agents to secure warrants to search private land merely by concocting an imaginary confidential informant who told police about some malfeasance.[16]

The core of the “open fields” decision is that the government cannot wrongfully invade a person’s land, because government agents have a right to go wherever they damn well please. After this decision, any “field” not surrounded by a 20-foot-high concrete fence is considered “open” for inspection by government agents. (And for those areas that are sufficiently fenced in, the Supreme Court has blessed low-level helicopter flights to search for any illicit plants on the ground.[17])

The Supreme Court decision, which has been cited in over 600 subsequent federal and state court decisions, nullified hundreds of years of common-law precedents limiting the power of government agents. The ruling was a green light for warrantless raids by federal immigration agents; in late 1997 the New York Times reported cases of upstate New York farmers’ complaining that “immigration agents plowed into fields and barged into packing sheds like gang busters, handcuffing all workers who might be Hispanic and asking questions later . . . . [D]oors were knocked down, and workers were wrestled to the ground.”[18] In a raid outside of Elba, New York, at least one INS agent opened fire on fleeing farm workers.[19] Many harvests subsequently rotted in the fields because of the shortage of farm workers.

Conflicting Views of Freedom

Conflicting Views of Freedom

The “open fields” doctrine provides an acid test of conflicting views on freedom. Are people more or less free when government agents can roam their land? Are they more or less free when they can be accosted by government agents any time they step past the shadow of their front door? Is freedom the result of government intrusions—or of restrictions on intruders? The scant controversy the 1984 decision evoked is itself a sign of how statist contemporary American thinking has become.

Few government policies better symbolize the contempt for property rights than the rising number of no-knock raids. “A man’s home is his castle” has been an accepted rule of English common law since the early 1600s and required law-enforcement officials to knock on the door and announce themselves before entering a private home. But this standard has increasingly been rejected in favor of another ancient rule—“the king’s keys unlock all doors.”[20]

A New York Times piece observed in 1998 that “interviews with police officials, prosecutors, judges and lawyers paint a picture of a system in which police officers feel pressured to conduct more raids, tips from confidential informers are increasingly difficult to verify and judges spend less time examining the increasing number of applications for search warrants before signing them.”[21] The Times noted that “the word of a single criminal, who is often paid for his information, can be enough to send armed police officers to break down doors and invade the homes of innocent people.”[22]

No-knock raids have become so common that thieves in some places routinely kick down doors and claim to be policemen.[23] The Clinton administration, in a 1997 brief to the Supreme Court urging blind trust in the discretion of police, declared that “it is ordinarily reasonable for police officers to dispense with a pre-entry knock and announcement.”[24] Law-enforcement agencies’ fear of losing small amounts of drug evidence has fueled attacks on the sanctity of homes. The Clinton administration, for instance, appears far more concerned about the flushing of drugs than about the flushing of privacy. In a 1995 brief to the Supreme Court, the Clinton administration stressed that “various indoor plumbing facilities . . . did not exist” at the time the common law “knock-and-announce” rule was adopted.[25] Making a grand concession to civil liberties, the administration admitted that “if the officers knew that . . . the premises contain no plumbing facilities . . . then invocation of a destruction-of-evidence justification for an unannounced entry would be unreasonable.”[26] The Supreme Court has failed to impose effective restraints on police’s prerogative to carry out no-knock raids. Professor Craig Hemmens observed that the Court’s “recent decisions involving the knock and announce rule, essentially gutted the rule, reducing it to little more than a ‘form of words.’”[27]

Police also possess the right to destroy property they search. Santa Clara, California, police served search and arrest warrants by firing smoke grenades, tear-gas canisters, and flash grenades into a rental home; not surprisingly, the house caught fire and burned down. When the homeowner sued for damages, a federal court rejected his plea, declaring that the police “only . . . carelessly conducted its routine and regular duty of pursuing criminals and obtaining evidence of criminal activity. The damage resulted from a single, isolated incident of alleged negligence.”[28]

It is as much a violation of property rights and liberty when government agents storm into the shabbiest of rental apartments as when they invade the richest mansion. The sanctity acquired by renters to a private domain illustrates how the exchange of private property can give someone vested rights—rights within which they can build and live their own lives. Local and state governments routinely treat renters as second-class citizens; many localities have mandatory inspection policies for all rental units that permit government officials to search private dwellings without a warrant or any pretext. Park Forest, Illinois, in 1994 enacted an ordinance that authorizes warrantless searches of every single-family rental home by a city inspector and police officer, who are authorized to invade rental units “at all reasonable times.” No limit was placed on the power of the inspectors to search through people’s homes, and tenants were prohibited from denying entry to government agents. Federal Judge Joan Gottschall struck down the searches as unconstitutional in February 1998, but her decision will have little or no effect on the numerous other localities that authorize similar invasions of privacy.[29]

It is as much a violation of property rights and liberty when government agents storm into the shabbiest of rental apartments as when they invade the richest mansion. The sanctity acquired by renters to a private domain illustrates how the exchange of private property can give someone vested rights—rights within which they can build and live their own lives. Local and state governments routinely treat renters as second-class citizens; many localities have mandatory inspection policies for all rental units that permit government officials to search private dwellings without a warrant or any pretext. Park Forest, Illinois, in 1994 enacted an ordinance that authorizes warrantless searches of every single-family rental home by a city inspector and police officer, who are authorized to invade rental units “at all reasonable times.” No limit was placed on the power of the inspectors to search through people’s homes, and tenants were prohibited from denying entry to government agents. Federal Judge Joan Gottschall struck down the searches as unconstitutional in February 1998, but her decision will have little or no effect on the numerous other localities that authorize similar invasions of privacy.[29]

Bane of Freedom?

Some socialists have argued that private property is a bane of freedom because inequality of wealth is equivalent to political tyranny. According to historian R. H. Tawney, “Oppression . . . is not less oppressive when its strength is derived from superior wealth, than when it relies on a preponderance of physical force.”[30] But regardless of how much wealth a person owns, he has no legal right to coerce other citizens. Offering someone the best wage he can find is unlike holding a gun to his head; offering someone the best price for a product he is selling is not like expropriation. A legitimate government must restrict the coercion of all citizens, including those with the largest bank accounts. But the fact that politicians are sometimes corrupted by bribes and deny equal protection of the law to the poor is not a good reason to give more power to politicians.

To understand the difference between economic wealth and political power, consider the difference between the power of a boss and that of a government agent. Any power that a boss or company has over a person is based on a contract, express or implied; that power is limited to the work and time contracted for. (Contracts for lifetime labor are illegal in the United States.) A boss’s power is conditional, dependent on an employee’s choosing to continue to receive a paycheck.

In contrast, the government agent’s power is often close to absolute: for example, a citizen who refuses to pull over for a traffic cop flashing his lights can face jail time, regardless of whether the cop had a legitimate reason to stop him. Markets allow people a choice of whom to deal with, while government dictates that citizens must submit to its orders. As Nobel laureate James Buchanan observed, “As individuals become increasingly dependent on ‘the market,’ they become correspondingly less dependent on any identifiable person or group. In political action, by contrast, increasing dependence necessarily becomes increasing subjection to the authority of others.”[31] Markets limit the power of people to dictate to other people because the parties can seek other bidders or sellers. Markets provide venues for people to voluntarily agree with other people. Markets are symbolic of voluntary activities in the same way that jails are symbolic of coercion.

Some friends of government legitimize vesting sweeping power in politicians by defining practically any private business decision as coercive. Economist Robert Kuttner declared on a 1997 PBS program that “when a company relocates overseas . . . that is a form of violence.”[32] To define practically any economic change as “violence” is to authorize an unlimited number of political first strikes against property owners. If moving a factory overseas is a form of violence, then moving a factory across state lines is also a form of violence—since the “violence” is presumably done by a factory leaving one location, regardless of where it relocates. When a person is given a “right” to a job, all other people are prohibited from competing for that job.

A viable concept of freedom must consist of more than psychological wish fulfillment—more than a fantasy world in which every citizen can buy low and sell high, in which every citizen gets the wages he demands and pays the prices he pleases. It is crucial to distinguish between frustrated economic aspirations and government coercion. Feeling a compulsive need to impress neighbors by buying a swimming pool is not the same as facing arrest for planting grass seed in your yard and allegedly disturbing a federally designated wetland. The compulsion to buy a suit of the latest fashion is not the same compulsion as experienced during an IRS audit, especially if the agent decides to employ a notorious “lifestyle audit,” which forces citizens to detail and justify how much cash they had on hand at any one time a year or two before, whether they have a safe deposit box and what it contains, how much they spend on groceries, where they eat out, what toys they buy for their children, and what books or jewelry they purchase.[33] The compulsion to buy a new car differs from the compulsion you feel when police pull you over, announce that your appearance matches that of a “drug courier profile,” and proceed to rummage through your trunk, glove compartment, tire hubs, and pockets, and to ask a bevy of incriminating questions about your personal life.[34] The fact that a person spends himself deeply into debt and thus feels obliged to keep working at a job he despises is not coercive because no one compelled the person to become a mindless consumer.

An inability to find a satisfactory job or satisfactory career path is not a violation of liberty—unless government or private action forcibly blocks or restrains people. A person is not “oppressed” by his own lack of marketable job skills: every art history major who did not find a good job after college is not a victim of some sinister force.

One of the clearest violations of freedom of contract is government licensing laws, which prohibit millions of Americans from practicing the occupation of their choice. Over 800 professions, from barbers to masseuses to interior designers to phrenologists to tattooists to talent agents, now require a government license to practice. Licensing laws are usually engineered by professional associations that want to “protect” the public from competitors who might charge lower prices.[35] Licensing laws kept many blacks out of the skilled professions until the civil rights era. The Federal Trade Commission perennially reports on the anticompetitive aspects of state government licensing boards.[36] For many professions, private accreditation systems—many of which have already been developed—would provide a much more reliable consumer guide than politically controlled certification systems.

Liberty in Action

Property is the basis of freedom of contract, which is simply liberty in action. Without freedom to exchange, government places all exchanges at the discretion of the political-bureaucratic ruling class. As new forms of property and wealth have developed in the last 200 years, it is now much clearer how vital property is to all citizens’ freedom, not merely that of landowners. By holding title to certain resources (including themselves and their own labor), people can make exchanges with others that allow them to raise themselves, to better provide for their families, to pursue their own values. Freedom is more than the right to own property or the right to buy and sell. But once the citizen loses the right to own—even if he previously owned nothing—he loses the ability to control his own life. If the citizen is denied the right to own or control his own computer disks or the clothes on his back, he has little chance of being able to shape his own future.

Property rights and market economies are vital steppingstones to political freedom. Private property gives people a place to stand if they must resist the government. Market economies and private property allow citizens to build up sufficient wealth to resist government pressure.

It is important to have freedom to buy and sell, to invest, to innovate, to choose one’s risks and reap one’s profits—but it is not enough. It is also vital that police not be able to break people’s heads, or entrap them on bogus charges, or intercept their e-mail at a whim, or target them because of their race, ethnicity, or political ideas. Unfortunately, some advocates of economic freedom seem nonchalant about practically any use of government power that does not directly interfere with profit-making.

Notes

- Quoted in James W. Ely, Jr., The Guardian of Every Other Right (New York: Oxford University, 1992), p. 26.

- Chicago, Burlington & Quincy R.R. v. Chicago, 166 U.S. 226 (1897).

- John Dewey, Liberalism and Social Action (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1935), p. 34.

- Jerome Gilison, The Soviet Image of Utopia (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1975), p. 149.

- Quoted in Robert Skidelsky, The Road from Serfdom (New York: Penguin, 1997), p. 99.

- Ibid., p. 119.

- James Bovard, “Eastern Europe, The New Third World,” New York Times, December 20, 1987, and James Bovard, “The Hungarian Miracle,” Journal of Economic Growth, January 1987.

- The Writings of James Madison, vol. 6, ed. Gaillard Hunt (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1906), p. 103. The quote is from an article Madison wrote for the National Gazette, March 29, 1792.

- Alan Wolfe, review of Stephen Holmes’s Passions & Constraint: On the Theory of Liberal Democracy, New Republic, May 1, 1995.

- Tom Bethell, The Noblest Triumph: Property and Prosperity Through the Ages (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998), pp. 272-89.

- James Bovard, “Assistance to Flood Victims Invites Further Disaster,” Los Angeles Times, June 18, 1997.

- Richard Epstein, Takings (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1985), p. 66.

- Oliver v. United States, 466 U.S. 170, 179 (1984).

- Ibid., p. 180, fn. 11.

- Ibid., p. 192.

- The National Law Journal reported in 1995 that between 1980 and 1993 the number of federal search warrants relying exclusively on confidential informants nearly tripled, from 24 percent to 71 percent, and that “from Atlanta to Boston, from Houston to Miami to Los Angeles, dozens of criminal cases have been dismissed after judges determined that the informants cited in affidavits were fictional.” Mark Curriden, “Secret Threat to Justice,” National Law Journal, February 20, 1995.

- Florida v. Riley, 488 U.S. 445 (1989).

- Evelyn Nieves, “I.N.S. Raid Reaps Many, But Sows Pain,” New York Times, November 20, 1997.

- Associated Press, “Agent Fired During Raid on Migrants, Report Finds,” New York Times, December 12, 1997.

- Craig Hemmens, “I Hear You Knocking: The Supreme Court Revisits the Knock and Announce Rule,” University of Missouri at Kansas City Law Review, Spring 1998, p. 562.

- Michael Cooper, “As Number of Police Raids Increase, So Do Questions,” New York Times, May 26, 1998.

- Ibid.

- Barney Rock, “Kicking in Doors New Trend among Thieves,” Arkansas Democratic Gazette, January 21, 1995.

- Hemmens, p. 584.

- Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae Supporting Respondent, Wilson v. Arkansas, no. 94-5707, February 23, 1995, p. 26.

- Ibid., p. 28.

- Hemmens, p. 601.

- Patel v. U.S., 823 F. Supp. 696, 698 (1993). For discussion of this case, see Gideon Kanner, “What Is a Taking of Property?” Just Compensation, December 1993.

- Kenneth Black et. al v. Village of Park Forest, 1998 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 2427, February 23, 1998.

- Quoted in Robert E. Goodin, Reasons for Welfare (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1988), p. 307.

- James Buchanan, “Divided We Stand,” review of Democracy’s Discontent: America in Search of a Public Philosophy” by Michael J. Sandel, Reason, February 1997, p. 59.

- “Debate on Free Trade,” Public Broadcasting Service, August 15, 1997.

- Arthur Fredheim, “IRS Audits Digging Deeper Beneath the Surface,” Practical Accountant, March 1996, p. 20.

- See, for instance, Tracey Maclin, “The Decline of the Right of Locomotion: The Fourth Amendment on the Streets,” Cornell Law Review, September 1990, p. 1258, and Mark Kadish, “The Drug Courier Profile: In Planes, Trains, and Automobiles; and Now in the Jury Box,” American University Law Review, February 1997, p. 747.

- See, for instance, Sue Blevins, “Medical Monopoly: Protecting Consumers or Limiting Competition?” USA Today (magazine), January 1998, p. 58.

- Interview with Federal Trade Commission spokesman Howard Shapiro, July 28, 1998.

Comments are closed.