From the May issue of The Freeman…

From the May issue of The Freeman…

The Folly of Federal Training

by James Bovard

his State of the Union address President Obama proposed an array of new federal job training programs. This was one of the more popular facets of his speech, and the usual media cheerleaders swooned. However, Uncle Sam has a long and dismal training record, and new federal programs would be almost guaranteed to repeat past follies.

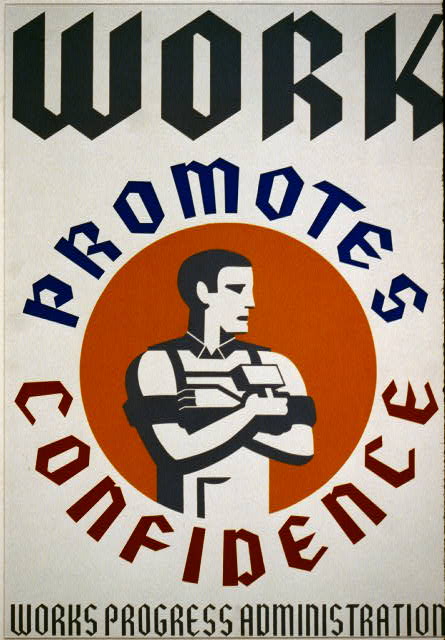

Franklin D. Roosevelt, with his Works Progress Administration (WPA), fathered modern government training and employment programs. When Roosevelt announced this relief program, the largest of the New Deal, he declared, “All work should be useful in the sense of affording permanent improvement in living conditions or of creating future new wealth.” FDR’s standards for WPA have been mocking government employment programs ever since. WPA, commonly known as “We Poke Along,” distributed paychecks to over three million people and is generally credited with giving leaf raking a bad reputation for an entire generation. By 1938 even FDR was embarrassed by his pet program.

The modern era of manpower law opened with the Area Redevelopment Act of 1961, a statute based on the “right” of geographical areas to equal economic development. The Area Redevelopment Administration (ARA) was established to direct federal money and training funds to depressed areas and was expected to play a substantial role in achieving full employment. Like subsequent federal training programs, ARA was based on the idea that jobs should come to people, rather than people going to jobs. ARA was thus the first of many training programs that discouraged individual adjustment.

Many of ARA’s targeted unemployed did not want to learn a new trade. As its first annual report noted, “One of the most serious obstacles was the fact that job opportunities in redevelopment areas were limited because of the long-term economic decline which characterizes those areas.” In ARA’s first year only 6,492 trainees enrolled—and fewer than 1,300 got jobs in fields related to their ARA training. Since unemployment exceeded five million when ARA was enacted, its impact was negligible.

The ARA’s goal was to “create jobs” and give training, but the General Accounting Office (GAO) found that the agency typically overreported the number of jobs created by 128 percent, did not use available information to evaluate the number of new jobs supposedly created, and routinely gave millions of dollars to locales that no longer had high unemployment. By 1965 the ARA had sufficiently discredited itself to be renamed the “Economic Development Administration.” (EDA was eventually also recognized as a four-star boondoggle and was abolished in the early 1980s.)

In 1962 Congress passed the Manpower Development and Training Act (MDTA) to provide training for workers who lost their jobs due to automation or other technological developments. MDTA was hailed by “manpower experts” as the great hope for American workers.

But although MDTA expanded throughout the 1960s, its success was confined largely to political speeches and statistical charades. In a 1972 report the GAO concluded that federal manpower programs were failing on every score—that youth programs were not reducing the high-school dropout rate, that valuable job skills were not being taught, that little effort was being made to place trainees in private jobs, that Department of Labor (DOL) monitoring of contractors was inadequate, and that little follow-up of trainees was occurring. GAO noted, “According to DOL, there is an overriding concern with filling available slots for a particular program rather than with developing the mix of services that the person needs

Renaming the Boondoggle

In 1973, faced with a confusing hodgepodge of floundering training programs, Congress passed the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA). In the preface to the new law Congress conceded that “it has been impossible to develop rational priorities” in job training. Existing federal programs were widely perceived as failures, and CETA was supposed to be the cure for all that ailed job training. However, most of the contractors and subcontractors under MDTA were simply given new, often more lucrative grants and contracts under CETA. The same agencies and nonprofit organizations repeated the same mistakes under a new acronym.

CETA began as a training and employment program, but job creation took precedence during the 1974–76 recession. Although the recession was over when President Jimmy Carter took office in 1977, he nonetheless ordered the creation of 350,000 additional public-service jobs by year’s end. Local government officials complained to Congress that the DOL was pressuring them to hire more people than they wanted; officials threatened to withdraw all funds if localities did not spend “another million by Friday.”

CETA gave $500 a month to a communist agitator in Atlanta to, in his words, “organize for demonstration and confrontation.” In Philadelphia 33 Democratic party committeemen or their relatives were put on the CETA payroll. In Chicago the Daley political machine required CETA job applicants to have referral letters from their ward committeemen and left applications without such referrals piled under tables in unopened mail sacks. In Washington, D.C., almost half the city council staff was on the CETA rolls.

CETA was often used to increase demand for other government services. In Maryland CETA workers offered free rides to the welfare office. In New York CETA workers ran a phone service to inform people what unemployment compensation benefits they were entitled to receive.

CETA spent over $175 million on art projects. This was not because CETA expected an increase in the demand for artists or because any inadequacy was identified in existing methods of training artists. CETA spent millions on the arts simply because it thought the arts were a nice thing and that taxpayers should have more of them, whether they liked it or not. In Montgomery County, Maryland, the richest county in the nation, CETA paid nine women $145 a week to attend ballet school. In Poughkeepsie, New York, CETA workers busied themselves attaching fake doors to old buildings to beautify the city.

CETA was a dismal failure for trainees. A DOL-funded study found that CETA recruits had “significantly lower post-program earnings” than similar individuals who never enrolled in CETA. Congress responded by replacing CETA with the Job Training Partnership Act (JTPA) in 1982. JTPA was more private-sector oriented than CETA, but it was still a creature of politics and bureaucracy. JTPA programs were advised and sometimes directed by local Private Industry Councils.

President Ronald Reagan often bragged that JTPA had a 68 percent job-placement rate for “economically disadvantaged” trainees, as proof of the success of a public-private partnership. Former labor secretary Ray Donovan called JTPA “one of the greatest achievements in the history of government social policy,” and his successor, Bill Brock, called it “a model for human resource programs.” The national 68 percent placement rate was concocted from 50 state measurements with no consistency or uniformity. JTPA’s placement figures were “largely one-day-on-the-job” figures, according to Gary Walker, a New York consultant who evaluated the program for the Ford Foundation.

Welfare for Business

JTPA’s success was a mirage: Instead of serving the hard-to-employ, JTPA was largely a welfare program for business. Most JTPA contractors also provided services under CETA. Once again, the main thing that had changed was the program’s name.

“Customized training”—designing a training program for the specific training needs of an individual company—was a popular JTPA activity. In Cincinnati JTPA paid for in-house training program costs previously assumed by General Electric. In Spring Hill, Tennessee, JTPA paid training costs at General Motors’ new Saturn plant. In New Jersey and Maryland special programs were set up to train people to work at McDonald’s restaurants. McDonald’s would have had to train people anyway. The only difference was who paid for the training.

Where JTPA was not paying for training that would have occurred anyway, it often paid for training for jobs that didn’t exist. In the mining region of Minnesota, unemployment reached 80 percent in some towns. With the decline of the American steel industry, demand for iron ore would remain depressed and new industries were unlikely to enter the area. Yet JTPA poured in money to retrain the locals and help them search for nonexistent jobs.

In Pittsburgh 96 percent of JTPA funds were spent on classroom instruction—even though classroom instruction was known to be the least effective training method. But it was much easier to stick clients in a classroom than to place them in private jobs, so employment and training bureaucrats often favored endless classroom training.

JTPA’s most bizarre feature was its “employment-generating activities.” The Private Industry Councils used tax dollars to advertise and procure federal contracts. Illinois used JTPA funds to set up Procurement Outreach Centers around the state to help local businesses chase federal contracts. In Sacramento JTPA paid for advice on loan packaging, taxes, and employer-employee relations for small businesses.

In 1993 the DOL released a study that revealed that JTPA, like CETA, “actually reduced the earnings” of broad groups of trainees. JTPA was especially vexing to young males, whose earnings after training were 10 percent lower than earnings of similar individuals who avoided the program.

In 1998 JTPA was replaced with the Workplace Investment Act. There is no evidence to presume that government wizards have learned how to square the circle, at least as far as designing effective training programs is concerned.

The federal government has tried every imaginable manpower scheme over 80 years and has failed dismally every time. It cannot create incentives to provide valuable, cost-effective training by doling out billions of dollars. The sooner government stops making false promises and giving people false hope, the sooner that young and low-income people can begin learning real skills in the private sector.

Federal job-training programs will almost always be either unnecessary or worthless. Either the government will be training people for jobs that the private sector would have trained them for anyhow—or the government will be training for jobs that don’t exist. Federal training programs have tended to place people in low-paying jobs, if trainees got jobs at all. If the programs have any effect at all, it is simply to help some low-income people get jobs instead of other low-income people. Rather than creating new training programs, Obama should abolish existing programs and cease promising more than the government can deliver.

Comments are closed.