The Justice Department has resumed racketeering with the “equitable sharing” racket – helping local and state police agencies plunder innocent citizens who are stripped of their property. The Washington Post condemns the revival with an editorial aptly headlined: “The Feds Get Back in the Stealing Business.”

For over 20 years, reformers have exposed horrendous abuses; several times, it appeared that asset forfeiture thieving would be finally curbed. Below is a piece I wrote in 2001 after an earlier betrayal of reform efforts. My final sentence was an exercise in pretended wishful thinking: “If the Bush administration wants to set a loftier tone in Washington, ending forfeiture abuses is one of the best places to start.”

American Spectator, April 2001

An End to Federal Plundering?

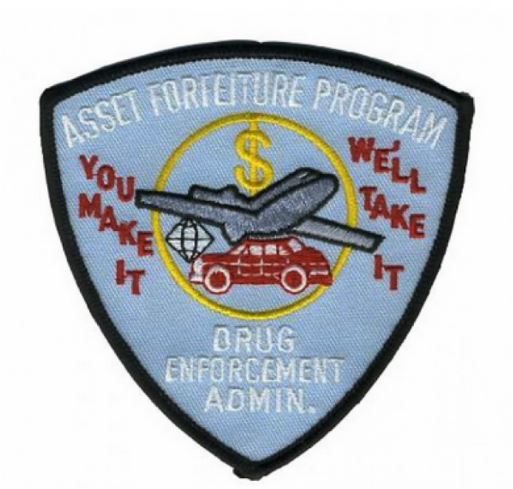

ASSET FORFEITURE: When the Feds arrest your property, innocence is no defense

BYLINE: James Bovard

Seizure fever continues to infect law enforcement across the nation. Last

August, the Albuquerque City Council passed a new ordinance empowering the

police to confiscate houses where they catch 20-year-olds drinking beer. Many

states and localities already have laws authorizing police to confiscate the

autos of people accused of drunk driving-regardless of whether a person is

convicted of the offense. In Minnesota, police confiscated a $ 40,000 sports

utility vehicle because the owner was sitting in the driveway testing the new

vehicle’s audio system after he got liquored up.

Roughly 70 percent of all U.S. currency has sufficient cocaine or other

narcotics residue to trigger a positive alert from a drug-sniffing dog,

according to numerous federal court cases. Yet the Wayne County, Michigan police

department confiscates the cash that people bring in to bail out friends or

relatives after dogs predictably alert-thus making it easy for police to pad

their own coffers. Federal agents continue to use this pretext to seize cash

despite numerous court rulings that the method is both unsound and unjust.

The Justice Department confiscated 42,454 cars, boats, houses, stacks of

cash, and other items of private property in 1998-booty valued at $ 604,514,

733. Federal agents can seize a person’s house, car, boat, or other property by

invoking more than two hundred different federal statutes involving everything

from wildlife to carrying cash out of the country to playing poker for cash with

friends and relatives. The vast majority of people whose property is seized by

federal agents are never formally charged with a crime. Some ninety percent

never get their property back.

How is that possible? Criminal charges against persons require proof beyond

reasonable doubt. But federal law, based on common law precedents reaching

back to medieval England, holds that when property suspected of use in a crime

is seized, the action amounts not to a criminal punishment of the owner- which

would require a trial on the reasonable doubt standard-but to an arrest of the

property itself, which enjoys no such protection. The owner’s attempts to get

his property back are then waged not under criminal rules, but under civil or

even administrative procedure dauntingly favorable to the government.

With accelerating forfeiture cases a national scandal at least since the

early 1990s, Congress last April finally passed a law purporting to curb some of

the worst abuses. Authored by House Judiciary Committee chairman Henry Hyde

(R-Ill.), renowned for his tendency to kowtow to law enforcement, the new law in

some ways tilts the playing field even further against innocent citizens.

Under the Civil Asset Forfeiture Reform Act, federal agents continue to have

the power to confiscate citizens’ assets without a court order and with no proof

of criminal wrongdoing. Federal agents merely need to claim ” probable

cause”-including rumor or hearsay evidence-before confiscating property. Only if

some citizen challenges the seizure must the government show by a “preponderance

of evidence” that the seizure was justified. ” Preponderance of evidence,” the

civil standard, means essentially that the government must show that there is a

51 percent chance that property was wrongfully used.

Since the vast majority of seizures are not challenged-tangling with federal

prosecutors is costly and beyond the skills of the sorts of lawyers available to

most victimized property owners-the new standard of evidence means little or

nothing to most forfeiture victims. The new law further intimidates challenges

by imposing a requirement that citizens who file suit to recover their property

must swear their claim is not “frivolous.” Any citizen who files an allegedly

frivolous suit can face three years in prison simply for filing it. Federal

agents suffer no penalties for frivolous seizures of private property; the

“punishment” for such behavior has in the past been outstanding performance

evaluations.

Will the Bush administration make federal agencies obey the law on

forfeiture? A good place to start would be the Customs Service, which scorns a

Supreme Court ruling that sought to limit their power to plunder travelers. The

1970 Bank Secrecy Act made it a federal crime for anyone to exit or enter the

United States with more than $ 10,000 in cash without filing a report with the

U.S. Customs Service. Customs agents pick out individuals heading for

international flights or bus trips and ask them if they are carrying more than $

10,000 in cash. If the person does not answer honestly, the agents routinely

seize the person’s money. In addition, the person faces several years in federal

prison for lying to a federal agent. Customs officials use the threat of prison

to persuade many people to forgo challenges to the seizure.

In 1998, Justice Clarence Thomas, writing for a 5-4 majority, struck down the

Customs Service’s confiscation of $ 357,144 from a Syrian immigrant who was

searched at Los Angeles International prior to heading back to Syria. The money

consisted of profits from his two gas stations and loan repayments for Syrian

relatives. Both a federal district court and an appeals court concluded that the

money had been honestly acquired and ordered most of it returned to the man.

Thomas declared that “a punitive forfeiture violates the Excessive Fines

Clause if it is grossly disproportional to the gravity of a defendant’s

offense.” The crime in question “was solely a reporting offense.” The maximum

fine under federal sentencing guidelines was $ 5,000. Thomas also noted that the

forfeiture of the cash “bears no correlation to any injury suffered by the

government.”

Customs’ response to the Court? It sharply escalated its efforts to

confiscate travelers’ cash, launching a crackdown called Operation Buckstop. In

April 1999, Customs Chief Ray Kelly bragged to Congress: “Outbound currency

seizures experienced a 59 percent increase in the amount of currency seized

compared to the same time period in FY 1997.” At Houston International Airport,

100,813 passengers were searched in 1998, though customs inspectors were able to

find pretexts to strip only eight people of their cash, including a Mexican

mother with a baby and $ 18,924.

The Feds apparently took another blow in court on January 17 when federal

judge Charles Sifton ruled that the federal government could seize cash in a

civil proceeding after it failed to challenge a finding by the court probation

department that the money was lawfully acquired. The case involved Cesar Castro,

who was arrested after he told a Customs agent at JFK International that he had

$ 2,000 with him; a search revealed that he actually had almost $ 120,000.

Castro was sentenced to two years probation and fined $ 2, 500.

After Castro’s conviction and sentencing, the government undertook a civil

action to confiscate Castro’s cash, though no evidence had ever been offered

that Castro’s money had any illegal taint. Castro had by then been through a

full criminal trial and sentencing procedure. Steve Kessler, Castro’s lawyer and

one of the nation’s foremost experts on forfeiture, told the New York Law

Journal that “the government has brought hundreds of forfeiture cases after

acquiescing to findings in pre-sentencing reports that the seized cash was

unconnected to any criminal activity.” In other words, after the government had

already tacitly admitted there was no basis for the seizure.

The greatest failing of last year’s forfeiture reform act was that it did

nothing to curb law-enforcement profiteering from forfeitures. Law enforcement

agencies routinely keep seized assets for their own uses-one of the most brazen

conflict-of-interests around. Forfeiture policies continue to be a grave blot

on the integrity and credibility of the federal government. If the Bush

administration wants to set a loftier tone in Washington, ending forfeiture

abuses is one of the best places to start.

Comments are closed.