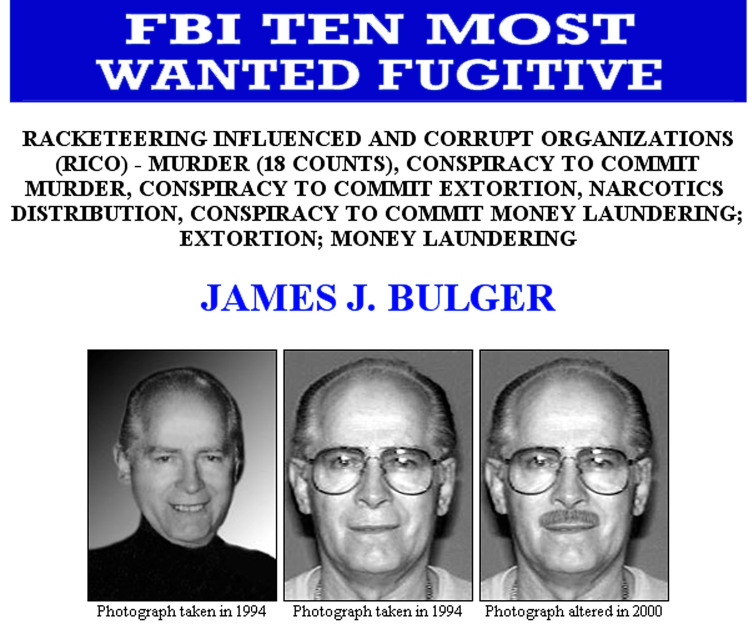

Whitey Bulger, the FBI’s most notorious informant, was found dead in prison today. He lived to be 89 – unlike the 20 people whose murder he was connected to. The FBI knew of his role in killings but lied in court to protect him. The FBI even helped send innocent men to prison for life to safeguard Bulger.

When this scandal began unraveled, the Bush administration rushed to assert “executive privilege” in 2001 to protect the reputation of the FBI and Justice Department. More details of FBI scandalous behavior eventually leaked out, especially during Bulger’s a dozen years later. A federal judge aptly labeled the case “official uncontrolled wickedness.” A former FBI agent “was convicted of second-degree murder for leaking information to Boston mobsters that led to the 1982 shooting death of a gambling executive who also had ties to gangsters.”

How many murderers is the FBI currently protecting? The FBI officially pre-approves its informants committing more than 5000 crimes per year. What could possibly go wrong?

Here’s an excerpt from my 2004 book, The Bush Betrayal, on the contortions that the Bush administration used to cover up FBI crimes:

PRIVILEGED TO CONCEAL; OR HOW BUSH PROTECTS LIBERTY

PRIVILEGED TO CONCEAL; OR HOW BUSH PROTECTS LIBERTY

On December 12, 2001, Bush announced that he was invoking “executive

privilege” to withhold subpoenaed documents from Congress because their

disclosure would be “contrary to the national interest.” Bush warned that the

congressional investigation threatened Americans’ cherished freedoms: “The

Founders’ fundamental purpose in establishing the separation of powers in

the Constitution was to protect individual liberty. Congressional pressure on

executive branch prosecutorial decisionmaking is inconsistent with separation

of powers and threatens individual liberty.”3

Bush invoked protecting individual liberty to cover up the FBI’s role in

mass murder in Boston and its perversion of justice throughout New England.

Beginning in 1965, the FBI enrolled Boston mob murderers as informants

and shielded these killers time and again from prosecutors seeking to nail

them. The FBI helped send four innocent men to prison for life for a murder

committed by one of the FBI’s favorites. (Two of the men died in prison.) The

FBI’s prize informant, “Whitey” Bulger, absconded in 1995 and was quickly

placed on the “Ten Most Wanted” list, thanks to his connection to more than

20 murders.

Bush’s invocation of executive privilege enraged Rep. Dan Burton (R-Ind.),

chairman of the House Government Reform Committee, who was leading

the investigation into FBI perfidy. When a deputy assistant attorney

general appeared before the committee the day after Bush’s statement, Burton

blasted the guy: “This is not a monarchy. . . . We’ve got a dictatorial President.

. . . Your guy’s acting like he’s king.”4

Burton notified Attorney General Ashcroft that “it eludes me how it is in

the national interest to cloak this dark chapter of the Justice Department’s history

in secrecy.”5 He later summarized the outrages: “The United States Department

of Justice allowed lying witnesses to send men to death row. It stood

by idly while innocent men spent decades behind bars. It permitted informants

to commit murder. It tipped off killers so that they could flee before they

were caught. . . . And then, when people went to the Justice Department with

evidence about murders, some of them ended up dead.”6

The House Government Reform Committee’s final report on its investigation,

released in November 2003, denounced the FBI’s conduct in New England

as “one of the greatest failures in the history of federal law enforcement.”

More than 20 murders were allegedly committed by FBI informants and

“major homicide and criminal investigations in a number of states including

Massachusetts, Connecticut, Oklahoma, California, Nevada, Florida and

Rhode Island were frustrated or compromised by federal law enforcement of-

ficials intent on protecting informants.” Countenancing murders by FBI informants

was not a rogue Boston operation; instead, awareness of the killings

extended “all the way up to the office of FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover.” The

committee also raised questions about “whether the FBI used its authority to

protect former Massachusetts State Senate President William Bulger [the

brother of ‘Whitey’ Bulger] from scrutiny by law enforcement or to advance

his political career.”7

The FBI office in Boston was continuing to deny any misconduct as late

as 2001—shortly before Bush invoked executive privilege. Though two of the

four people wrongfully sent to prison for life because of the FBI were still alive,

the Justice Department treated this as an irrelevant closed case.

The Bush administration eventually dropped its claims of executive privilege

and provided foot-dragging cooperation. The committee noted that “the

President’s claim of executive privilege was a drastic departure from the longstanding history of Congressional access to precisely the types of documents

sought by the Committee.” Congress had routinely had access to such documents

going back to the Teapot Dome scandal of 1923.

No FBI agent was ever disciplined, let alone fired, for his role in fomenting

and condoning mass murder in Boston. After the committee issued its report

in November 2003, the FBI issued a statement: “While the FBI recognizes there have been instances of misconduct by a few FBI employees, it also recognizes the importance of human source information in terrorism, criminal and counterintelligence investigations.”8 The FBI did not specify how many murders it would countenance in the future by its informants.

The administration had tactical reasons to stonewall Burton’s investigation.

The Hill, a Capitol Hill newspaper, noted that even relatively ancient

“revelations [of FBI misconduct] would be problematic for Ashcroft at a time

when he is pushing to significantly expand the powers of law enforcement as

part of the war on terrorism.”9 In a May 2002 announcement that he was unleashing

FBI agents to conduct surveillance in any “public” place they choose

(including churches, mosques, and political meetings), Ashcroft boasted: “In

its 94-year history, the Federal Bureau of Investigation has been . . . the tireless

protector of civil rights and civil liberties for all Americans.”10 At the time

of Ashcroft’s declaration, the Justice Department was still using trick after trick

to block congressional discoveries of FBI atrocities. And in its response to the

Burton investigation, the Bush administration did not hesitate to invoke the

highest principles to cover up dastardly deeds. For Bush, preserving the good

reputation of government was more important than exposing and deterring

FBI profound and perennial abuses.

Comments are closed.