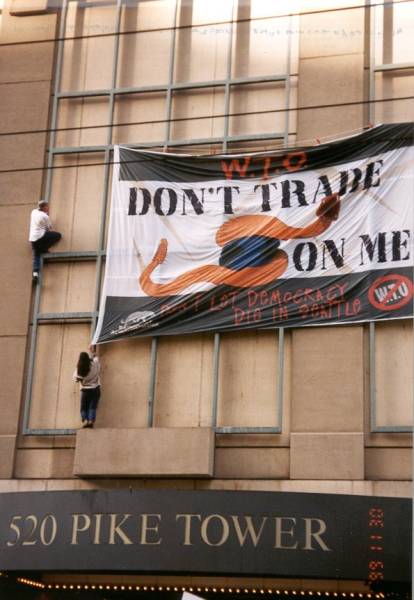

Reasonable folks are naturally appalled at the trade rhetoric and trade wars coming out of the Trump White House. Trump is sometimes portrayed as a shocking deviation from U.S. government support for free trade. In reality, Bill Clinton’s trade policies shared many of the same protectionist follies. Clinton’s showboating and legacy lust paved the way to street battles over trade in Seattle 20 years ago – with plenty of police brutality and excesses thrown into the mix. Here’s the analysis of that debacle from Feeling Your Pain (St. Martin’s Press, 2000), followed by an article from the American Spectator. And a hat tip to the photographers among the demonstrators (or spectators) who kindly put some excellent photos on Wikipedia.

SABOTAGE IN SEATTLE (from Feeling Your Pain)

In late 1993, in the final days of the Uruguay Round of trade talks, U.S. Trade Representative Mickey Kantor had a brilliant idea: to change the name of a toothless international oversight body from the General Agreement on Tariffs

and Trade to the World Trade Organization (WTO). Kantor, a former Hollywood lawyer, wanted an organization name that would befit Clinton’s delusions of grandeur. (The Bush administration indulged in similar foolish labeling: if the North American Free Trade Agreement had been simply called a “limited tariff reduction agreement between three countries,” it would not have become a lightning rod. However, Bush needed a campaign issue, so the NAFTA label stuck. NAFTA was not really a free-trade agreement: instead, it was an agreement to give preferential treatment to imports from two nations, thus disadvantaging imports from other nations.)66

Both GATT and the new WTO consisted largely of binding arbitration panels that heard and ruled on trade disputes between member nations. Neither GATT nor WTO could bomb Belgrade since they were simply a bunch of desk workers with no air force, navy, or nukes. Many critics feared that the WTO would turn the United States into a fiefdom. But the WTO cannot violate U.S. sovereignty because it possesses no tools to impose its decisions on the U.S. government. The WTO cannot force the United States to change any law (though it could authorize other nations to impose limited penalty tariffs on U.S. exports if the United States refused to comply with a WTO panel ruling).67 If the WTO suddenly morphs into an organization that subverts U.S. national interests, the United States can exit at the drop of 51 senators’ hats.

There was no consensus or broad demand in early 1999 for another round of international negotiations to reduce trade barriers. But the planners in Clinton Legacy Central were hungry for something to solidify Clinton’s reputation as a world leader. Since the end of World War II, the United States had taken the lead in launching international negotiations to lower trade barriers. One hundred thirty-four nations responded to the Clinton administration’s sum-mons to gather in Seattle to launch “the Clinton round.”

The name WTO proved, as should have been expected, a lightning rod for opponents of capitalism, trade, and modern civilization. A few weeks before the summit, Clinton declared, “I’m actually kind of glad all these demonstrators are coming to Seattle, even though it may be kind of messy, because we ought to have a big global debate on this. And the people who feel like they’ve been shut out ought to be brought in and listened to, not just the environmentalists but the others as well.”68 Clinton rolled out the red carpet to the anarchists and others that turned downtown Seattle into a tear-gas-streaked, rubble-strewn battleground.

Clinton detonated the meetings even before he arrived. In a telephone interview with the Seattle Post-Intelligencer published on the opening day of the talks, Clinton declared that a WTO working group “should develop these core labor standards, and then they ought to be a part of every trade agreement, and ultimately I would favor a system in which sanctions would come for violating any provision of a trade agreement.”69 Clinton thus made clear what U.S. Trade Representative Charlene Barshefsky had long denied: that he wanted a new agreement that authorized imposing penalty tariffs on imports from any nation that did not pay a global minimum wage. White House aides later tried to brush off the comment by claiming that Clinton was speaking merely “in an aspirational way.” Clinton’s comment stunned delegates. India’s minister of commerce and industry later told his country’s parliament that Clinton’s remark was “the last straw . . . It made all the developing countries and least-developing countries harden their position. It created such a furor that they all felt the danger ahead.”70

Clinton sacrificed the WTO talks for domestic political advantage. He sought to impress U.S. labor unions with his hostility to imports from low-wage countries and to assure environmentalists that he would allow them to disrupt trade whenever they raised sufficient hell in the streets. Clinton sought to turn the entire meeting into a photo opportunity for Vice President Gore’s flounder-ing presidential campaign.

Clinton continued to pander to the demonstrators even after they had hassled, assaulted, and denounced the delegates to the convention on the streets of Seattle. In his first speech in Seattle, Clinton declared, “They are knocking on the door here, saying, let us in and listen to us.” Clinton declared that the delegates must “be prepared to give an answer” to the demonstrators.71 Many of the leftist demonstrators foamed as if the WTO was the trade policy equivalent of “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.” Yet Clinton never challenged the demonstrators’ key assertions and made no effort to refute them.72

Clinton’s machinations were aided by trade-illiterate members of the press corps. The New York Times idiotically reported that Clinton sought to build a reputation as a “free trader with a social conscience”73 and that he pushed for the Seattle meetings because he “was convinced that he had one free-trade victory left.”74 As long as White House aides kept telling journalists on background that Clinton, deep down, still wanted free trade, it did not matter how many lame-brained protectionist schemes he proposed.

Clinton’s shenanigans in Seattle may have done permanent damage to the WTO. Clinton’s Seattle fiasco greatly energized the enemies of free trade.

The American Spectator, February, 2000

And Clinton’s showboating and legacy lust paved the way to street battles over trade in Seattle 20 years ago. Here’s an article I did shortly after that ruckus.

The American Spectator, February, 2000

Clinton Trashes Trade

Seattle was merely his most visible protectionist moment.

BYLINE: by James Bovard.;

James Bovard is the author of Freedom in Chains and The Fair Trade Fraud, both

published by St. Martin’s Press.

President Clinton’s pretenses of being a free-trader exploded in flames in Seattle last December. The amazing thing was that anyone ever saw him as anything more than an old-time protectionist-opportunist. From the start, his administration sought maximum political and bureaucratic manipulation of trade–the same prescription Clinton favored for health care, the environment, antitrust, and countless other areas. While it’s true that Clinton did push through the NAFTA and GATT treaties early in his first term, both treaties had been largely negotiated by the Bush administration, and most of the Clintonite changes made to them left both treaties more protectionist.

In his 1998 State of the Union address, Clinton boasted, “In the last five years, we have led the way in opening new markets, with 240 trade agreements that remove foreign barriers to products bearing the proud stamp ‘Made in the USA.'” In reality, more than 160 of those agreements were actually one-sided edicts compelling foreign governments to restrict the amount of clothing they sold to American consumers.

Clinton has fought doggedly to preserve and expand U.S. restrictions on textile imports. The feds impose import quotas on 3,000 textile products,including tampons, typing ribbons, tarps, twine, towels, tapestries, and ties. The combination of high U.S. tariffs and import quotas add the equivalent of a 50 percent tariff surcharge to the price of imported clothing. Protectionism is addictive, and Clinton’s textile policy has been an unending series of alarms over incursions by perfidious foreigners. Consider the following actions from the administration’s first two years:

* In early 1993 Clinton announced that the U.S. would likely be sending

ground troops to protect Macedonia against a possible Serb attack. Yet a few

weeks later it was Clinton’s Commerce Department that attacked the country. At

the time, Macedonia was exporting men’s and boys’ wool suits to the U.S. at an

annual rate of 240,000 and faced no restrictions. The Commerce Department

slashed import levels by 67 percent to 80,000 wool suits a year. So much for

Macedonia’s most important export to the United States.

* In January 1994, Commerce Secretary Ron Brown visited Egypt and publicly criticized the government for its slowness in pursuing market reforms. A few days after Brown left Egypt, the Commerce Department announced plans to slap

import quotas on Egyptian shirts. The announcement sparked a furor in Cairo and threatened to disrupt the delicate Middle East peace process.

*In February 1994, the Clinton administration carried off the largest panty

raid in history. Silk imports have never faced high trade barriers because the

U.S. has no silk worms and produces no silk clothing. But as silk clothing

imports surged in the early 1990’s–making such items affordable for the first

time to the average consumer–the administration fretted these imports might

undercut the sale of cotton and polyester American-made clothes. Clinton

imposed severe restrictions on silk from China, where almost all the exports

originated.

*On May 18, 1994, the Commerce Department announced that Americans would be

prohibited from purchasing more than 1.5 million Kenyan pillowcases in the

following year. At the time, Kenyan pillowcases accounted for less than one

percent of American pillowcase purchases.

*On September 19, 1994, the U.S. invaded Haiti–dropping troops on the

island only hours after its military junta agreed to resign. Five days later,

the administration re-imposed quotas on exports of Haitian clothing and

textiles–the island’s largest employer and leading earner of U.S. dollars.

Clinton was willing to risk the lives of 20,000 American soldiers–but was

unwilling to risk the profits of a single American textile manufacturer.

Deprived of Haitian-made clothes, the U.S. taxpayer would underwrite Haiti’s

losses as the administration deluged the island with foreign aid–including $45

million to protect the Haitian currency against instability and $25 million to

pay Haiti’s foreign debts.

* In 1994, the U.S. pledged $700 million in economic aid to Ukraine. But after

$18 million worth of Ukrainian wool coats penetrated the American mainland that

year, the Commerce Department imposed quotas in November 1994, effectively

freezing future exports of one of the few competitive Ukrainian products at 1994

levels. The U.S. action helped revive Soviet-style central planning–as the

government now dictated the number of coats specific factories were permitted

to expor tto the U.S.

The administration did make one major concession to free-trade activism at

this time. On May 4, 1994, the Commerce Department announced that soccer teams

arriving in the U.S. for World Cup matches would be permitted to bring

foreign-made clothes for personal use with them.

How fair are U.S. fair trade laws? In recent years Japan and the European Union have bitterly complained about U.S. anti-dumping laws. Dumping is supposed to mean that a foreign company is selling for less in the U.S. than at home, or for less than its cost of production. But that’s not how it’s seen by the Commerce Department, which now routinely convicts foreigners for charging Americans unfairly low prices. Under Clinton, Commerce has ruled against foreign companies in 98 percent of dumping cases–ranging from Chilean salmon, to Chinese pencils and paper clips, to Romanian steel pipes, to Italian pasta, to Taiwanese roofing nails, to German printing presses, to Indonesian mushrooms. These rulings, which led to the imposition of heavy penalty tariffs, effectively locked hundreds of foreign companies out of the U.S. market.

Dumping penalties also damage the competitiveness of America’s leading industries. A Congressional Budget Office study noted, “Most U.S. antidumping activity–approximately four-fifths of active measures and approximately two-thirds of the products covered by the active measures–is against upstream goods (i.e., inputs).” Dumping cases have inflated the price American businesses must pay for semiconductors, computer flat panels, steel, railroad rails, and ball bearings.

While President Clinton never tires of lecturing about the need to respect diversity and to adore multiculturalism, much of his trade policy has come down to old-fashioned Jap-bashing. From 1993 to 1995, the Clinton administration was obsessed with forcing Japan to agree to compulsory quotas on purchases of American autos, auto parts, and other products. Regarding trade with Japan, in early 1994 Clinton announced, “I would like to have a focus on specific sectors of the economy, and I would like to obviously have specific results.” In May 1995, his administration announced plans to slap 100 percent penalty tariffs on 13 Japanese luxury cars to compel the Japanese to set specific quotas for the sales of U.S. autos and auto parts in Japan. Although Clinton trade officials backed down at the last minute in that fight, in early 1999 they successfully browbeat the Japanese to impose quantitative restrictions on their steel imports to the U.S.

In late 1993, in the final days of the Uruguay Round of trade talks, U.S. Trade Representative Mickey Kantor had a brilliant idea: change the name of a toothless international oversight body from the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) to the World Trade Organization (WTO). Kantor, a former Hollywood lawyer, wanted a name that would befit Clinton’s salvation rhetoric and delusions of grandeur. Similar thinking was responsible for calling the WTO to Seattle last fall. In early 1999 there was no consensus or broad demand for another round of international trade talks. But planners at Clinton Legacy Central were hungry for a photo opportunity–something to canonize Clinton’s reputation as a world leader.

One hundred thirty-four nations responded to the U.S. summons to gather in Seattle for “the Clinton round.” No doubt most expected that the U.S., as it has since the end of World War II, would lead the way in lowering trade barriers. But those weren’t the signals Clinton was sending.

Even before the talks convened, leftist organizations and other opponents of capitalism and free trade promised to turn the meeting into a sham. Clinton welcomed their presence: “I’m actually kind of glad all these demonstrators are coming to Seattle,” he said two weeks before the summit, ” even though it may be kind of messy, because we ought to have a big global debate on this. And the people who feel like they’ve been shut out ought to be brought in and listened to….”

If that weren’t enough, he dropped this bomb. In an interview with the Seattle Post-Intelligencer published on the talks’ opening day, Clinton declared that a WTO working group “should develop these core labor standards, and then they ought to be a part of every trade agreement, and ultimately I would favor a system in which sanctions would come for violating any provision of a trade agreement.” Clinton had made it clear that his highest goal was a new agreement that imposed penalty tariffs on imports from any nation that did not pay a global minimum wage. Clinton called it a “workers’ rights” provision; in reality, it was a non-competition clause. Clinton’s demand was similar to what protectionists have demanded for more than 130 years–except that before Clinton no modern U.S. president had ever called for banning the products of poor nations from American markets. It was an act of bad faith to summon delegates to a trade liberalization summit–and then announce on day one that most of their nations would get shafted. But at least the debacle was music to the ears of Al Gore and his Big Labor supporters.

After delegates had been hassled, assaulted, and denounced by protesters, Clinton arrived and declared delegates must “be prepared to give an answer” to the demonstrators. True to form, he made no effort to rebut the demonstrators he helped incite. In the chaos, it was overlooked that Clinton also helped scuttle the talks by refusing to address European and Japanese calls for the reform of U.S. dumping abuses.

Clinton’s machinations were aided by a trade-illiterate press corps. The New York Times idiotically reported that Clinton sought to build a reputation as a “free trader with a social conscience” and that he pushed for the Seattle meetings because he “was convinced that he had one free-trade victory left.” As long as White House aides kept saying on background that Clinton, deep-down, still wanted free trade, it did not matter how many lame-brained protectionist schemes he proposed.

Clinton has probably done permanent damage to the WTO. An attempt to compel the U.S. to withdraw from the WTO is expected early next spring in the Senate. The Seattle fiasco greatly energized the enemies of free trade–which may be Clinton’s final legacy.

Comments are closed.