The Greatest Tariff Speech in Congressional History

by James Bovard, November 19, 2024

Donald Trump is bringing his idolatry of high tariffs back to the White House. Trump proclaims that “tariffs are the greatest!” and that “tariff” is “the most beautiful word in the dictionary.” Vast numbers of his Republican supporters will echo any dubious dogma that Trump sanctifies.

In the coming months, Washington will be deluged with convoluted economic analyses vindicating or damning high tariffs. To vanquish the new protectionism, the friends of free trade should recall the lofty rhetoric from an era when the tariff was debated with far more clarity and passion.

High tariffs became American policy in 1861, after Abraham Lincoln and the Republican Party captured the White House and Congress. Southern states relied on agricultural exports and desired to purchase the best manufactured products available at the lowest prices. The Republican Party soared to power spurred by contributions from factory owners who sought captive customers south of the Mason-Dixon line for their often inferior products.

After seven southern states seceded, congressional Republicans rushed to enact a prohibitive tariff bill even before Lincoln took office. A New York Times editorial on February 14, 1861 warned that boosting the tariffs as high as 216% could drive the border states out of the Union: “One of the strongest arguments the [seceded states] could address to [border states] would be furnished by a highly protective tariff on the part of our Government, toward which they cherish the deepest aversion.” The Times condemned the bill as a “disastrous measure” that “alienates extensive sections of the country we seek to retain” and will “deal a deadly blow…at the measures now in progress to heal our political differences.” The Times’ astute arguments were ignored by Republicans willing to risk Civil War in order to blockade American ports to foreign goods.

In the first decades after the Civil War, Republican politicians relied on invoking “the bloody shirt”—blaming the Democratic Party for the Civil War and keeping hatred alive among voters. By the 1880s, as the bloody shirt lost its effectiveness, the tariff became the dominant political issue. Republicans continued raising the tariff long after the Confederacy had been conquered.

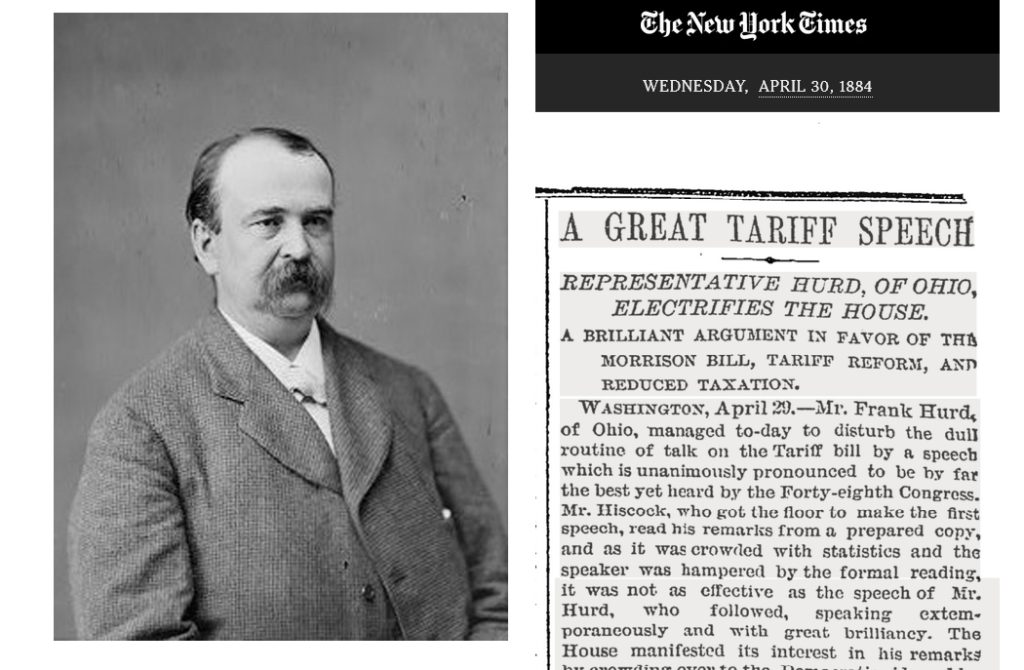

On April 29, 1884, Rep. Frank Hurd, a Democrat who served three non-consecutive terms in the U.S. House of Representatives, took to the floor for an hour to pound protectionists to smithereens. A New York Times headline hailed, “A Great Tariff Speech; Representative Hurd of Ohio Electrifies the House. A Brilliant Argument in Favor of the Morrison Bill, Tariff Reform, and Reduced Taxation.”

Hurd’s anti-tariff rhetoric was inspired in part by the war that had been belatedly justified for ending slavery:

“I deny the right of the Government to build up one man at the expense of another…By the power of the law I have been compelled to work one day against my will for the benefit of the American manufacturer. All of my effort and all of my toil for that day have been made his. In other words, for one day I have become his slave…He might just as well have awakened me in the morning hour and under the whip and spur and the lash have compelled to me work for him until the setting of the sun as to do what he has done. Every dollar of increase of price which the protective tariff occasions is a day of slavery, and every hour of unnecessary labor that it requires is stolen from invaluable time of individual responsibilities and duties.”

Hurd denounced the “war-taxes” tariffs and exposed how closing the borders ravages personal independence:

“I rest my whole case upon this proposition, that subject to the necessities of the Government, every man has a right to sell where he can get the best price for what he has produced, and to buy where he can buy the most cheaply. It individualizes men; it begets in them a spirit of independence; it turns their eyes from the Government to themselves. It fixes the boundary line between governmental power and personal right. It limits the authority of public administration. It teaches men that there is no arm so strong for their support as their own arm, and there is no business so successful as that which their own abilities and skill have established. In a word, it limits government to its proper sphere, and leaves individuals free to choose their own career, develop their own resources, and build up their own fortune.”

Hurd estimated that the tariff “increases the price of articles imported into this country 43 percent on the average,” thereby allowing domestic producers to hammer American consumers. Hurd exposed how blind faith was the ultimate source of protectionist fervor. He scoffed at the prevailing ignorance:

“What is the effect of the tariff upon those manufacturers who have the protection of the tariff alone? I have been surprised at the want of knowledge exhibited by manufacturers with whom I have talked upon this subject. When I have asked them how the protective tariff affected them, I have found very few who could tell me exactly the increase of price which the tariff made to them impacted their business. And when I asked them how much it affected the price of their product at any particular time they were almost always unable to tell. When I have inquired how much the tariff increased the prices of their raw material and plant, and of the articles they were obliged to have in order to manufacture, I have found scarcely any who had given attention to this point.”

Hurd derided manufacturers who “will not read the statute-books of their country in order to learn how the laws of the land affect them.” But those same manufacturers swore that any reduction in the tariff would ruin them.

Hurd deftly obliterated the moral pretenses for protection:

“If a man’s business be a profitable one, it does not need the protection of the Government. If it be an unprofitable one, it furnishes a good reason why he should not continue it; but there is no reason why he should compel his fellow-citizens to pay higher prices for the articles he manufactures in order to make good his losses in a business into which he has voluntarily entered.”

Hurd taunted his congressional opponents:

“Will the Republican object, when he remembers that it was his party that passed the tariff law during the days of the war, when a promise was made to the country that the tariff should be abrogated as soon as the war was over, that it was simply a temporary measure?”

Hurd condemned any “policy that would degrade and oppress labor by unjust and unequal laws.” He concluded by portraying the battle over protectionism as the supreme moral battle of the era:

“Private extortion must yield to public right. Selfish interests must be sacrificed to the general good, and each individual’s manhood must be left free, unhindered, and unhelped by Government, to work out its own destiny. And in the glorious result of the struggle I am sure that this protection giant of robbery and oppression will disappear from the land, never again to offend America by his presence nor to darken its fair fields with his shadow.”

The New York Times praised Hurd for “disturbing the dull routine of talk on the tariff bill.” There were other congressmen who had superb salvos on that issue in 1884. Senator James Beck of Kentucky declared, “The tariff is the protection the wolf gave the lamb.” On April 15, 1884, Rep. William Morrison of Illinois asked, “Why should restrictive legislation distribute the advantages of all human progress as applied to popular well-being among the favorites of Congressional legislation?” He scoffed at the endless tariff increases:

“Duties sufficient for protection in 1861 ought to be more than sufficient after twenty-five years. It is a cardinal faith of the protectionist, so far as he has any faith not measured in dollars and cents, that protection cheapens production, strengthens productive power, and lifts its favorites from less dependence upon the bounty of the Government.”

But the clamor for perpetual high tariffs proved the fraud of such claims.

Flash forward one hundred and forty years, and Donald Trump is again making “magical thinking” about tariffs fashionable. Econometrics will not suffice to defeat the latest attempt to derail world trade. To vanquish the new protectionism, the friends of free trade will need to recapture the moral high ground that champions like Congressman Frank Hurd illuminated long ago.

Comments are closed.