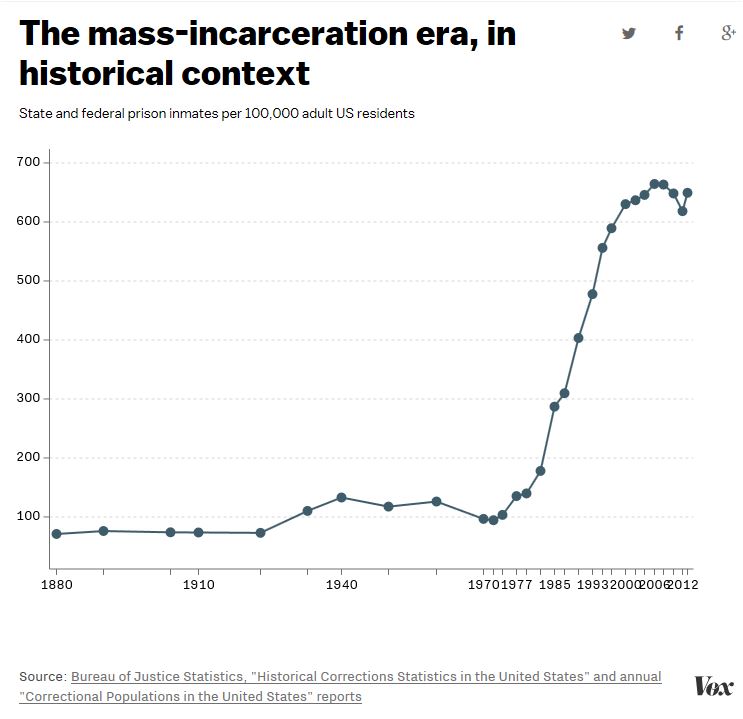

Vox has a great chart today on the soaring rate of prison incarceration in recent decades. This is one of the most striking renditions I have seen of this particular seachange in the relationship of government to the American people. Hillary Clinton bemoans high incarceration rates but the Clinton administration plowed almost $8 billion into prison building around the nation. The 1994 crime bill that Bill Clinton pushed into law worked out great for prison guards.

Playboy, February 2002

HEADLINE: Pork barrel prisons: who profits from the war on drugs?

by James Bovard

The war on drugs staggers on. Since 1980, the number of people locked in jails and prisons has quadrupled, breaking the 2 million mark last year. A lawmaker in Louisiana observed that things had become so bad his state had “half the population in prison and the other half watching them.”

We continue to read stories of draconian sentences, of racist enforcement polices, of police brutality and violence, of families shattered by the crusade against marijuana and so-called hard drugs. The grim statistics have prompted calls from journalists, judges, governors, police chiefs, mayors and lobbies such as Families Against Mandatory Minimums to end the war–to no avail.

Why the resistance to rethinking the war on drugs? The answers are not simple, but consider these two factors: money and jobs. In the past six years, the federal government has awarded $8 billion to pay for building state penal facilities. Call it a bribe. As it swells local coffers, the flow of money to small towns and depressed areas corrupts the public conscience. A Florida state brochure estimates that “a prison with 1158 beds is worth $25 million a year and 350 jobs to a community.” In Lexington, Kentucky, authorities promised this past year that two new prisons in the area would invigorate the local economy. Never mind that the drug laws there fill those prisons with nonviolent offenders. America needs its new cars, its fat construction contracts and jobs, any jobs, even those built on injustice.

Profiteering has political rewards that go beyond pork barrel greed: It creates and maintains clout. Towns that have a new prison built in their domain–or annex land that includes a nearby prison–can see their “population” double or triple. Many federal grants are based on raw population figures, regardless of how many residents live in jail cells. Prisoners become tokens redeemed for funds for public housing, roads and environmental and social programs. Officials in Luzerne Township, Pennsylvania celebrated when their area was chosen for a prison: It meant $4 million worth of sewer improvements.

Local governments also collect federal windfalls because most prisoners have zero income, thus making the locales appear to be poverty zones. Florence, Arizona receives almost two thirds of its budget from federal grants keyed to the number of convicts within town limits. Prisoners are definitely a cash crop.

The Wall Street Journal noted recently that the prison phenomenon also is reshaping the political landscape: “Although inmates aren’t allowed to vote in most states, they are counted for legislative apportionment and redistricting. In states such as New York, the prison boom has helped shift political muscle from minority-dominated inner-city neighborhoods to rural areas dominated by whites.”

In the Seventies New York governor Nelson Rockefeller, a Republican, launched the zero tolerance, mandatory minimum, lock ’em up and throw away the key approach to drug offenders. It is no coincidence that 40 of the 41 prisons built in New York since 1983 have been placed in Republican senatorial districts. The City Project reported in March 2000 that 26 of the state’s 71 prisons enrich the districts of just three Republican senators–the chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, the chairman of the Crime Victims, Crime and Corrections Committee and the chairman of the Codes Committee.

Last year, activists challenged Governor George Pataki to turn just one of those prisons into a drug treatment center. Don’t hold your breath.

Every jail needs its keepers. Since 1980, the number of people employed as prison guards and other correctional employees has grown from fewer than 100,000 to more than 400,000. In some states prison-guard unions have done far more to rig the political game than the contractors who build prisons, or the private companies that run some of them. The California Correctional Peace Officers Association is the most powerful lobby in the state, or at least the most generous, donating more to legislators than any other entity. In 1998 the CCPOA gave more than $2 million to aid gubernatorial candidate Gray Davis, who, after winning the election, quickly approved more than half a billion dollars for building new prisons. Davis’ political appointees also gave the union $4 million from the state treasury.

Prison guards have milked the political system to turn themselves into a blue-collar aristocracy, with the senior guards pulling down salaries of $52,000, plus ample overtime. Not a few guards earn more than some professors at the University of California. The CCPOA has used its political muscle to push through numerous laws to create perpetual full employment for its members. In 1994 the union spearheaded a campaign for the three-strikes law that has resulted in life sentences for many relatively small-fry offenders. A state corrections official estimated that passage of the three-strikes bill would necessitate the building of 20 penitentiaries in the following six years.

The CCPOA ran a big media campaign against the commonsense and compassionate Proposition 36, which directed the state government to send people convicted of nonviolent drug offenses to treatment facilities instead of prison. Thanks in part to the CCPOA, California incarcerates drug users at a rate far higher than the national average. Thanks in part to the prison union anticrime juggernaut, California has since 1980 passed more than a thousand bills that impose harsher sentences.

The CCPOA, which is derisively referred to as the prison thugs union by Californians who fail to share the union’s idealism, has flexed its muscle to give its members almost unlimited power over prisoners. Local district attorneys almost never prosecute prison guards for killing or beating inmates, out of fear of the CCPOA’s wrath. A district attorney who tried to prosecute a prison guard lost his seat to a candidate the union helped with campaign contributions. When legislators sought to transfer jurisdiction for prison-guard brutality to the state’s attorney general, the CCPOA torpedoed the bill. The CCPOA also successfully sued the Department of Corrections and the Department of Justice to prevent the questioning of any prison guard without 24 hours’ notice.

The CCPOA blocked a bill that would have required random searches of prison guards for drugs, lest any of their members find themselves on the other side of the bars. Union boss Don Novey said that drug trafficking was limited to only five or 10 “ignorant” guards. Internal affairs investigations have detected scores of guards in the drug business.

The CCPOA keeps its eyes open for potential competitors–most notably the private prison industry. “Prisons for profit threaten our professionalism,” says the union’s legislative policy specialist. Besides, government prisons are much easier to unionize–and to control indirectly through the CCPOA’s leash on legislators. In 1998 private prison companies donated $285,000 to state candidates in California. All told, that same year, the CCPOA donated more than $4.5 million.

The CCPOA is not the only heavyweight union in the prison business. The union representing New York prison guards was the second-largest donor to state politicians in the first half of 2001, according to the New York Public Interest Research Group. The union for Illinois prison guards demanded that the state hire an additional 500 guards last year. A new union has formed to represent Pennsylvania’s 9500 prison guards; the Pennsylvania State Corrections Officers Association may attempt to mimic the tactics and enjoy the success of the CCPOA.

Money does corrupt. Drug war money corrupts absolutely, blinding politicians to the traditional duties of government. In Mississippi, drug warriors found they had more prison beds than convicts to fill them. Lobbyists for private prison companies, along with local sheriffs with jail space and the county governments, hustled state legislators to pass a bill to pay subsidies for “ghost inmates” to compensate prisons for the shortfall of bodies. The Wall Street Journal noted that legislators somehow found the money for ghost inmates at the same time they were cutting state budgets for classroom supplies, community colleges and mental health services.

Some states are realizing that ever-growing prisons create more problems than they solve. Reform legislation in Oklahoma aims to focus prison spending on “people we’re afraid of as opposed to those we’re just aggravated with,” explained state senator Dick Wilkerson.

Last June, a California judge, responding to a lawsuit, temporarily blocked the state Department of Corrections from breaking ground for a new 5000-bed prison.

Enough is enough.

Comments are closed.