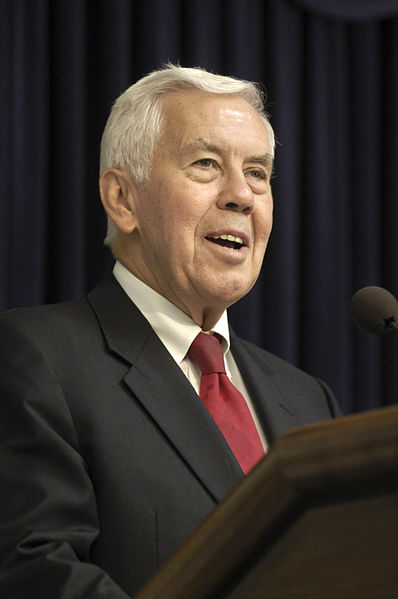

Former senator Richard Lugar died yesterday at age 87. He was from Indiana and he understood farm policy far better than most members of Congress. I briefly met him a time or two; he and I were both speakers at a farm credit conference in Nashville in the early 1990s. (My other memory of that conference: a single puff on a cigar was sufficient to trigger the smoke alarms in the smoking rooms in the hotel.) Lugar seemed like a decent fellow without the swagger and venality that trademarks so many congressmen.

Former senator Richard Lugar died yesterday at age 87. He was from Indiana and he understood farm policy far better than most members of Congress. I briefly met him a time or two; he and I were both speakers at a farm credit conference in Nashville in the early 1990s. (My other memory of that conference: a single puff on a cigar was sufficient to trigger the smoke alarms in the smoking rooms in the hotel.) Lugar seemed like a decent fellow without the swagger and venality that trademarks so many congressmen.

In 1990, the George. H.W. Bush administration held budget talks at the White House. Politicians and aides sought suggestions on reducing the federal deficit (sounds like a notion from an antediluvian age but it was only last century). One of his top aides told me that Lugar held up a copy of my 1989 book, The Farm Fiasco, during one session and cited its recommendations for slashing farm spending. There was no evidence the gesture made any converts. Instead, Bush broke his “no new taxes” pledge and paved the way for the election of Bill Clinton as president in 1992.

Lugar was a responsible man so he didn’t embrace my call to abolish farm subsidies across the board. But he did call for effectively ending export subsidies, peanut subsidies, the sugar program, and other four-star boondoggles. He was also outspoken criticizing disastrous farm credit subsidies which produced bumper crops of bankruptcies in rural America.

In The Bush Betrayal (2004), I quoted Lugar’s condemnation of the 2002 farm bill (which provided subsidies for the next 5 years). Lugar declared that the bill creates “a huge transfer payment from a majority of Americans to very few” and also warned that the lavish new subsidies would result “almost inevitably” in “vast oversupply and lower prices.”

Here are a few ag policy articles in which I quoted Lugar.

The Wall Street Journal

Tuesday, May 21, 1996

Farm Loans: Only Bad Risks Need Apply

By James Bovard

For the last 57 days, federal agents and a group consisting largely of disgruntled farmers have

been in a standoff outside Jordan, Mont. While the stranger aspects of the self-proclaimed

Freemen’s ideology have been widely reported, little attention has been paid to the role of the

Agriculture Department in paving the way to this confrontation. Regrettably, federal farm subsidy

policies have been even loonier than the Freemen themselves.

Ralph Clark, an illiterate grade-school dropout, is the mastermind of the Freemen. He and his

partners have received more than $650,000 in farm subsidy payments since 1985, according to the

Environmental Working Group, a Washington advocacy organization. In addition, Mr. Clark has

personally received almost $2 million in federal farm loans since the late 1970s. Most generously,

the federal government kept sending him annual payments of almost $50,000 to reward him for

not growing on the land he bought with government loans — long after he effectively defaulted on

those loans.

Why did Mr. Clark receive so many government loans? Because he was uncreditworthy.

Why did Mr. Clark receive so many government loans? Because he was uncreditworthy.

According to the Farmers Home Administration, this alone entitled him to a windfall. And, since

he kept losing money time and again, that proved that he needed — and deserved — new loans.

In fact, Mr. Clark symbolizes the type of farmer favored by the Farmers Home Administration: big

— with a 7,000-acre government-paid spread — and incompetent. Mr. Clark was a poster boy for

farm aid lobbyists in the 1980s, portrayed sympathetically in Life magazine, with Geraldo Rivera

on ABC’s “20/20” and elsewhere. But, since then, his racism and raving anti-Semitism have

become overt, and his appeal with the Willie Nelson crowd has suffered.

For many farmers, the road to hell has been paved with cheap government credit. “If you want to

increase efficiency of a farm enterprise, give them a low-interest loan and they’ll be an efficient

farmer,” Rep. Steve Gunderson (R., Wis.) declared in 1986. FmHA has encouraged many

struggling farmers to continue farming until they destroy themselves financially. According to the

agency’s own records, by far the most frequent cause of bankruptcy among its borrowers is “poor

farming practices.” The General Accounting Office estimated that a quarter of FmHA

bankruptcies occurred because the farmers received too much subsidized credit. “In some cases,

continued FmHA assistance has actually worsened the financial condition of farmers who have

entered the program,” the GAO noted in 1992.

Since 1989, the FmHA has been hit by more than $12 billion in loan defaults and other losses. In

1994, the Clinton administration forgave $138 million in losses from 74 farm borrowers — almost

$2 million per farmer. In many cases, federal officials made scant effort to collect on the loans, or

to compel borrowers to surrender other assets to cover the government’s financial bloodbath. The

GAO reported in 1995 that FmHA in recent years gave $500 million in new loans to farmers who

previously defaulted on government loans. The GAO estimated in 1992 that almost three-quarters

of FmHA’s $20 billion in outstanding farm loans could default.

Uncle Sam has long believed that uncreditworthy farmers deserve capital on much better terms

than their more competent, experienced neighbors. One current federal program reduces the

interest rate for uncreditworthy borrowers by four percentage points; this gives them a huge

advantage over unsubsidized farmers. Besides, FmHA loans have long been treated as gifts. “I

believe that the USDA has created a system that actually provides an incentive to not repay the

loans it makes,” Rep. Bob Wise, (D., W.Va.) complained in 1992.

In 1994, Sen. Richard Lugar (R., Ind.) challenged Clinton administration officials over the

profusion of million-dollar-plus loans to FmHA borrowers. Though the administration promised

speedy reform, the problem has worsened: In the most recent survey, almost 40% of farmers with

direct FmHA loans were delinquent — a delinquency rate more than 10 times higher than that of

the average private bank.

Thanks to Sen. Lugar’s efforts, some of the worst absurdities of farm lending have been curbed;

unfortunately, the government will remain heavily involved in providing loans to uncreditworthy

farmers. Under the recently passed farm bill, the Agriculture Department is authorized to make

more than $20 billion in direct and guaranteed loans to farmers in the next six years; further multi-

billion-dollar losses are likely. While congressmen brag about how farm programs are being

phased out, subsidized lending to farmers is actually scheduled to increase between now and

2002. And Midwest Senate Democrats are on the warpath, pushing a bill to defend every farmer’s

sacred right to further loans after defaulting on the government.

But the Clinton administration has learned from the recent farm lending debacle. The name of the

Farmers Home Administration was changed in 1994 to the Consolidated Farm Service Agency.

The Clintonites thereby upheld a hallowed tradition: FmHA’s predecessor agency, the

Resettlement Agency, generated so much bad press that in 1946 it was rechristened the FmHA.

And now, after FmHA has worn out a legion of auditors, its name has also been retired to the

Agricultural Boondoggle Hall of Fame.

Hopefully the Freeman standoff will end peacefully and that a federal jury will pass judgment on

Mr. Clark and his cronies. Unfortunately, taxpayers will never get a chance to pass judgment

directly on the congressmen and bureaucrats who masterminded the deluge of bad farm loans —

thereby proving once again that, in Washington, it is safer to squander tens of billions rather than

to steal a few million.

—

Mr. Bovard writes often on farm issues.

********************

The Wall Street Journal

Monday, July 29, 1985

We Shell Out a Peck for This Nutty Program

By James Bovard

Amazingly, consumers may soon get a break on the 1985 farm

bill. When the Senate considers the agricultural bill this

week, Sen. Richard Lugar (R., Ind.) intends to offer an

amendment to terminate the current peanut program. If Sen.

Lugar’s amendment passes, the farm lobby’s phalanx will be

broken, and other farm programs might be defeated.

Sen. Lugar is targeting perhaps the most obnoxious farm

program around. It slashes productivity, boosts costs,

inflates prices, and sacrifices some farmers to other

farmers. If consumers are ever to make a stand in the farm

bill fight, the peanut program is a good place to begin.

Farmers cannot grow peanuts for their fellow citizens

without a federal license. Thirty-six years ago, to reduce

budget outlays under a generous price-support program,

Congress closed off the peanut industry, distributing

licenses to grow peanuts to existing farmers and prohibiting

anyone else from entering the business. Feudalism still

reigns, and the farmer who violates the peanut proscription

is subject to heavy fines and ensnarement in the Agriculture

Department bureaucracy.

The peanut program is particularly perverse because

Congress has piled on one restriction after another over the

years. In 1977, Congress, in an attempt to reduce budget

outlays caused by peanut surpluses, began restricting the

amount of peanuts to be sold in the U.S. The domestic peanut

supply has been nearly halved since 1975. This has created an

artificial shortage and shifted the cost of the peanut

program from the government to consumers.

The peanut program is replete with the usual ag policy

flim-flams. By law, peanut support prices must be based on

cost of production (COP). The Agriculture Department gets

this “fair price” by averaging costs of the most productive

and least competent farmers. The implicit premise is that no

matter how badly a farmer bungles his business, he is

entitled to be reimbursed (in part) for his efforts.

In 1980, peanuts were hit by drought, which sharply

reduced yields and thereby temporarily boosted per-pound

production costs. Congress based its 1981 COP calculation on

the 1980 drought year — which conveniently justified a 21%

hike in price supports, from $440 to $555 a ton.

The COP figure is also a joke because the peanut program

itself adds as much as 50% to a farmer’s cost of production.

Approximately half of all growers rent licenses to grow

(called quota allotments) from outsiders, paying a tribute of

up to $120 a ton for the right to grow goobers. The cost of

renting allotments is added to the COP formula, which results

in higher price supports, which drives up the rents for the

privilege to grow peanuts, which results in higher COP . . .

ad infinitum.

The quota system is also responsible for exhausting the

soil and driving down peanut yields in many places. Quota

allotments cannot be rented outside of the county they were

originally allocated to in 1949. Peanut yields in parts of

Texas have long been declining. While many acres with yields

below 1,000 pounds have quotas, over a million acres with

potential yields of 2,500 pounds or more are banned from

producing for the domestic market.

The restrictions on renting quotas outside the original

county have turned a program to protect peanut farmers into a

program to protect local tax bases.

The one good thing about the peanut program is also the

element that proves that the whole shebang is unnecessary. As

of 1981, any farmer could grow peanuts for export (called

Additional Peanuts) — but with no real price guarantees from

Uncle Sam. Peanut export sales are now far above mid-1970s

levels. Georgia farmers are growing peanuts for export at

$325 a ton — at the same time that Congress insists on

paying farmers $555 a ton to produce for domestic

consumption. Foreigners can buy U.S. peanuts much more

cheaply than Americans can.

Though it is good that more farmers have finally been

allowed to grow peanuts, the two-tier system sacrifices the

newcomers to the old guard. By strictly limiting the domestic

quota, the Agriculture Department reduces U.S. peanut

consumption and thereby dumps a few hundred million tons of

extra peanuts on the world market. This depresses prices

received by American farmers growing peanuts for export.

The two-tier system is absurd. Peanut butter made from

quota peanuts can be exported to Canada and Mexico, but

peanut butter made from additional peanuts cannot. (The

Agriculture Department fears the cheaper peanut butter made

from additional peanuts could be re-imported.) The additional

peanuts themselves can be exported to Canada, and American

peanut butter manufacturers are paranoid that Canadian

companies might be using cheap peanuts to make peanut butter

and then sending it back across the border. According to

congressional testimony, peanut-exporting companies are

required to closely supervise their peanuts until they cross

the border, which adds about $20 a ton to handling costs.

Congress gives peanut growers a far better deal than other

farmers receive. An American Peanut Product Manufacturers

Institute study estimated that peanut price supports “have

been set 80% above USDA-defined production costs . . . when

land costs are excluded, and 60% above when the inflated

costs of land are included.” The Institute differs with the

Agriculture Department’s method of calculating peanut

production costs. APPMI estimates that net returns to peanut

farmers are four to 10 times higher than returns from

competing crops.

Consumers are, as usual, the victims of this farm program.

The Agriculture Department estimates that the peanut program

boosts peanut butter prices 13.5%. Public Voice for Food and

Health Policy, a Washington consumer group, estimates that

the peanut program mulcts consumers for $250 million to $300

million a year.

There is hope for reform. The peanut program was almost

knocked off in 1981. That year, Rep. Stan Lundine (D., N.Y.)

proposed terminating the program, and the House approved

250-159. Sen. Lugar proposed phasing it out, and the Senate

initially approved, 56-42. (The Senate later reversed itself,

51-47, and Rep. Lundine’s bill vanished in conference.) Now

both Rep. Lundine and Sen. Lugar will try again. APPMI, other

peanut-product manufacturers, and Public Voice are vigorously

lobbying to persuade Congress to end the goober madness. The

peanut program’s opposition is stronger and better organized

this year and appears to have a good chance of success. And

if the peanut program can be knocked down, a domino effect

could occur with the rapid demise of the honey, wool and

sugar programs.

The peanut program artfully combines the worst traits of

feudalism and central economic planning. Congress has a

chance to end this program that makes a mockery of

efficiency, fairness and property rights.

—Mr. Bovard writes frequently on farm and other U.S.

programs.

+++

Lugar called out the hypocrisy of U.S. complaints on foreign wheat subsidies –

The Washington Times

January 26, 1994, Wednesday, Final Edition

HEADLINE: U.S. pasta-makers strain trade goals

BYLINE: James Bovard

BODY:

American farmers earlier this month blockaded a grain elevator in Shelby,

Mont. The reason for the blockade: The elevator was purchasing wheat from

Canada, which the American farmers considered the equivalent of an act of

treason.

The farmers, flaunting signs demanding, “Stop the Canadian Grain,” hope to

stampede the Clinton administration into action. But, if the Clinton

administration kowtows to the farmers’ demands, this will signal a betrayal of

all the Clinton, Bush, and Reagan administrations sought to achieve in

liberalizing agricultural trade.

The farmers are angry over a surge of durum wheat from north of the border.

Durum wheat is used for pasta products, certain breads and pastries, cereals and

other basic food items. Canadian imports of pasta have increased in recent

years and now account for roughly 25 percent of U.S. consumption. To add

insult to supposed injury, Canadian durum wheat is often higher quality than

American durum because of Canada’s cooler growing climate and Canadian

grain-handling practices.

Sen. Max Baucus of Montana proclaimed, “Canadian [unfair] practices put

Japan to shame.” Nine farm-state senators sent a letter to Agriculture Secretary

Mike Espy, demanding an “immediate initiation … of trade action to restrict

U.S. imports of Canadian wheat.” Agriculture Undersecretary Gene Moos told the

Senate Agriculture Committee Sept. 21 that he had formally recommended that the

president “consider an emergency proclamation establishing quotas on the imports

of Canadian wheat.”

Farm-state senators have picked an unfortunate time to denounce imports,

since U.S. durum wheat prices – more than $4.50 a bushel – are far above

federal target prices (prices picked by congressmen to guarantee most farmers

a generous profit). Yet American farmers are infuriated because the government –

after guaranteeing good prices – does not also give them a domestic monopoly.

While Northern Midwest senators busily denounce Canadian imports, their

states may be hurt more by the sharp cutbacks in wheat production caused by

federal acreage idling programs. U.S. production of durum wheat has nosedived

since 1981, falling from 5.8 million acres annually to just more than 2 million

acres in 1993. The Conservation Reserve Program (CRP), under which government

pays farmers to idle their land for 10 years, is the largest single set-aside

program. Sen. Kent Conrad of North Dakota complained in 1992 that the CRP has

“absolutely wiped out small town after small town as we took land out of

production.”

Even though U.S. farmers are not even growing enough durum to meet U.S.

consumption, the U.S. government is still lavishly subsidizing the export of a

large portion of the U.S. harvest.

The combination of falling U.S. production of durum and artificially

increased demand for durum caused by the export subsidies has driven the U.S.

durum price far above the world price. Naturally, the high prices have been a

signal to foreign producers that the U.S. market needs more durum. Sen.

Richard Lugar judiciously observed: “The credibility of our programs falters

if somehow someone writes a story that the federal government is deliberately

raising domestic [wheat] prices and then suddenly accusing the Canadians of bad

faith.” (Mr. Lugar opposes import quotas on Canadian wheat).

If the U.S. restricts Canadian wheat imports, the U.S. price of durum will

likely spike higher. This would put American pasta makers at an even greater

disadvantage against imports. Foreigners can buy U.S. wheat much cheaper than

can American food manufacturers, thanks to U.S. export subsidies. Industry

experts predict that if Mr. Clinton restricts Canadian wheat imports, some U.S.

pasta-making plants will move to Canada and many jobs will be lost.

American farmers complain that the Canadian wheat exports are unfair because

the Canadian farmers receive government subsidies. But U.S. farmers are also

wallowing in government largess. Since 1991, American wheat farmers have

received almost $7 billion in subsidies, and the Clinton administration

estimates that wheat subsidies will continue at almost $2 billion a year through

1998. In 1991, federal farm policy forced American taxpayers and consumers to

pay wheat farmers subsidies equal to 78 percent of the total value of the wheat

produced in the United States, according to the Organization for Economic

Cooperation and Development.

It is to be hoped that American farmers will be able to resist following the

worst examples of protesting French farmers, such as setting live British sheep

on fire to protest mutton imports. While most of the media coverage of the

farmers’ blockade was sympathetic, no one apparently asked the farmers how much

in federal subsidies they had received. This type of illiterate news coverage

simply encourages the worst abuses of the farm lobby.

Mr. Clinton should not export the U.S. food manufacturing industry by

restricting wheat imports. The U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC), at

Mr. Clinton’s behest, is conducting a formal investigation studying the effects

of the Canadian imports on the costs of U.S. farm subsidy programs. Rather

than taking emergency action, the Clinton administration should wait till the

ITC makes its formal request. Better still, Mr. Clinton should take emergency

action in defense of American taxpayers and abolish all U.S. wheat subsidies.

James Bovard is the author of “The Fair Trade Fraud” (1991) and the

forthcoming “Lost Rights: The Destruction of American Libert” (St. Martin’s

Press, April 1994).

Lugar favored ending or at least radically rolling back the sugar program:

States News Service

December 9, 1994, Friday

HEADLINE: SUGAR PROGRAM’S FUTURE UNCERTAIN UNDER REPUBLICAN CONGRESS

BYLINE: By Juliet Eilperin, States News Service

BODY:

Now that they’ve managed to take control of Congress, Republicans are

promising deep cuts in agriculture programs. If they chose to dismantle sugar

price support policy, however, they should prepare for a bruising fight.

The battle that has raged for two centuries will continue in the 104th

Congress, as soft drink and candy manufacturers spar with sugar growers. And

members of Congress rarely mince words when sugar users challenge the status

quo.

When Sweetener Users Association President Tom Hammer argued in 1990 that the

government guarantees a profit for sugar beet growers, Sen. Kent Conrad, D-N.D.,

urged him to join him on a trip back home and make the same claim before the

growers. Taking a page from the Jesse Helms play book, Conrad warned Hammer

that he would be wise to bring along protection: “We probably would have to have

the 82nd Airborne.”

Republicans are less likely to kill the sugar program, congressional staffers

predict, because it does not drain the federal treasury. The program also

enjoys widespread political support: roughly half the states in the U.S. have

sweetener producers, ranging from cane farmers to corn growers.

But critics argue the policy gouges consumers by imposing limits on imports,

contradicting America’s renewed commitment to free trade.

Members hailing from South Florida, where sugar production continues to make

an impact on the local economy, have traditionally fought for the federal

program. In Palm Beach County, the industry directly accounts for the

equivalent of 19,000 full-time jobs, and produces $839 million in raw sugar each

year.

States News Service, December 9, 1994

Under the current program, the government sets a minimum price for sugar,

lending money to processors which they repay with interest in nine months. If

they cannot sell the sugar at that price, the government must buy the remaining

sugar and sell it, but without taking a loss. This scenario has never happened,

primarily because the government sets import quotas to keep U.S. prices stable.

The program will survive, sugar producers say, because it keeps farmers in

business, makes money for the government and helps consumers.

“If you cut the sugar program, you might even hurt the deficit,” said Florida

Sugar Cane League executive vice president Dalton Yancey, noting that under the

program, the federal government collects interest payments and assessment fees

from the industry.

Several economists, however, insist American consumers would be better off

buying sugar at the world price, which is less than half as high as the American

one. In a study commissioned by the Save Our Everglades coalition, University

of Connecticut professor Rigoberto A. Lopez estimated the program had cost

Americans an average of $137 million annually between 1970 and 1974. A U.S.

Department of Agriculture official said the American price for sugar would fall

if the import quotas were lifted, whether or not other countries liberalized.

States News Service, December 9, 1994

Sugar industry executives question these kinds of studies, noting the price

of sugar has risen dramatically in the periods when the U.S. abandoned its sugar

policy, and producers dump sugar on the world market at an artificially low

price.

But economist James Bovard said Americans can afford to take the risk.

“This is the old hobgoblin protectionists always use,” he said. “It’s a

guaranteed loss now versus a slight risk loss in the future.”

Incoming Senate Agriculture Committee Chairman Richard Lugar, R-Ind., seems

to agree. During a press conference Friday, he compared the policy to the

mohair subsidy Congress eliminated last year.

“Why should sugar production be protected and imports restricted if the

result is higher sugar prices for American consumers?” he asked.

Bob Buker, vice president of U.S. Sugar, said Americans would be happy to

compete on the open market, as long as European governments stop subsidizing

their growers.

“We’re not for unilateral disarmament,” Buker said, adding that farmers would

be wiped out of business if the U.S. lifted its quotas in the immediate future.

Furthermore, Buker argued, lowering sugar’s price would only help industrial

users, like the soft drink and candy manufacturers. They would never pass on the

savings to consumers, he predicted, and the U.S. would then end up at the mercy

of foreign producers.

As Buker points out, industrial users and sugar producers — not consumers —

are busy debating the nation’s sugar policy. The two groups contribute heavily

to members of Congress: sugar political action committees gave nearly $160,000

to members of the Florida delegation between Jan. 1, 1991, and June 30, 1994,

according to the Center for Responsive Politics. Food and beverage

manufacturers gave even more money to Congress, and both groups show up to

testify when Congress reconsiders the legislation.

One congressional source in the Florida delegation said the sugar program

would remain intact in the 1995 farm bill because of its merits. The staffer

acknowledged, however, that industrial users and the sugar industry would play

key roles in the fight.

Save Our Everglades co-chair George Barley said the sugar industry’s

extensive political contributions have given it more influence than it

deserves.

“The federal government acts like this is a 4,000 pound gorilla,” Barley

said.

Comments are closed.