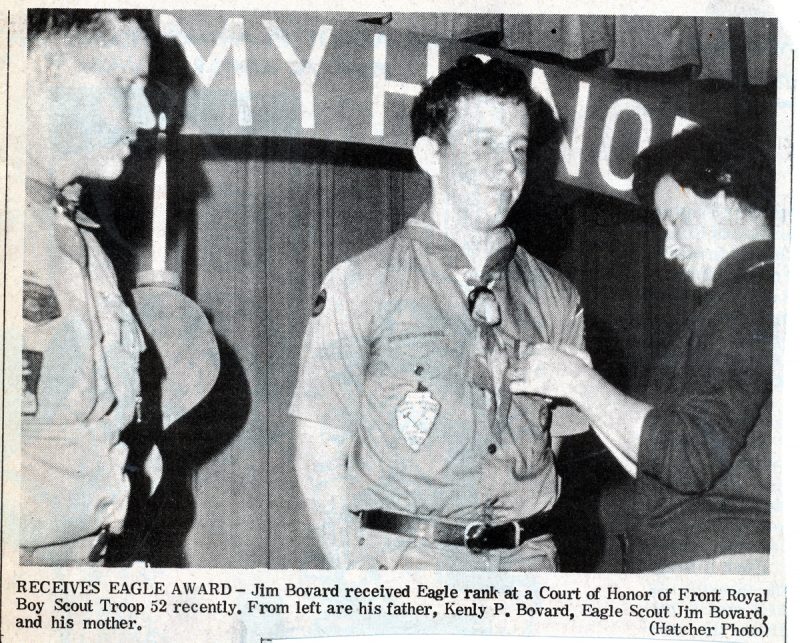

Fifty years ago today, I received the Eagle badge in Boy Scouts. If I had a dollar for every person in subsequent decades who was shocked or appalled that someone like me could have reached Eagle, I could buy several kegs of the best beer in Maryland. Likewise, it would be fun to know how many girls and women I dated over the decades invoked it as mitigating evidence to their parents: “He’s not all bad, y’know. He was an Eagle Scout.”

I want to express my appreciation to my father, Ken Bovard, who was Scoutmaster for the first two years I was in Troop 52, and to my mother, Mary Ellen Bovard, whose support and nourishment throughout my Scouting years was invaluable. (All those durn patches to sew on – she had a hundred times more patience than I ever did). I also want to thank the other adult leaders in Troop 52 in Front Royal, Virginia – Wendell Hatcher (who was Scoutmaster when I finished the qualifications for Eagle), and assistant scoutmasters Ken Fortune, Walter Duncan, Jr., “Slim” and “Hoss” Feldhauser, Bob Arnold, and other fine guys. I also want to thank the Methodist Church in Front Royal for sponsoring the troop.

The highlight of the award ceremony was the three minutes I fruitlessly spent trying to close the Eagle Award necklace around the back of my mother’s neck. I was confounded by the durn locket and finally apologized and just handed it to her. I was starting to bulk up at that point and a friend mentioned that I looked like the cartoon character Baby Huey in that uniform.

The Scouts have taken some wrong turns in recent years, and the systemic coverup of sexual abuse by adult scout leaders is an outrage. I hope the Scouts can survive the surge of lawsuits and reach higher ground in the coming years.

As I noted in a 2015 USA Today oped, “The skills I most enjoyed learning in the Scouts – building fires, camping in winter, shooting white water rapids in a canoe – involved getting your hands dirty and surviving bumps and bruises. While attending a National Scout Jamboree in Idaho, I also learned how much I dislike marching in step with thousands of other people. Scouting taught me to view minor hardships simply as transaction costs for great adventures.” Scouting got me off my ass and out into the woods – a legacy which continues to shape my life. My experiences traveling with a council-wide troop to a Jamboree in Idaho, where I forged my first press pass, probably sowed some seeds of my skepticism towards officialdom, a development which later spur plenty of publicity to conniving federal agencies and politicians. The lessons I learned in Scouting proved invaluable when I spent a summer hitchhiking and camping around Europe in my early 20s.

Here are the comments on Scouting I made in my last Father’s Day letter to my father, after he was diagnosed with leukemia in 2001: “I appreciate the time you invested and the sacrifices you made for Troop 52. Being a Boy Scout taught me a lot about the value of flexibility and marching on despite the cold, the rain, and the occasional Dutch Oven lashed to the back of my knapsack. Your high spirits and songs during the most inclement weather set a great example for me and many other boys. Learning how physical hardship could be ignored and overcome is a lesson that is worth more than words can say. The trip to the Idaho Jamboree in 1969 – which I took with encouragement from you – was an eye-opener that helped breed a hunger to discover what lay beyond the boundaries of Warren County.”

Here are the USA Today columns I have written about how my experience in Scouting helped shape me, for better or worse:

Trump’s Boy Scout speech may have set kids on the right path

President Trump telling Boy Scouts that Washington is a “sewer” could actually be an antidote to much of what they are taught on following authority.

Much of the media was shocked and horrified by President Trump’s Boy Scout Jamboree speech on Monday. Many commentators are talking as if Trump’s raucous, free-wheeling spiel exposed underage children to political pornography. Instead of railing against Hillary Clinton and boasting of his victory in last year’s election, Trump supposedly should have delivered the usual “our wonderful political system” speech.

Much of the media was shocked and horrified by President Trump’s Boy Scout Jamboree speech on Monday. Many commentators are talking as if Trump’s raucous, free-wheeling spiel exposed underage children to political pornography. Instead of railing against Hillary Clinton and boasting of his victory in last year’s election, Trump supposedly should have delivered the usual “our wonderful political system” speech.

Some people will never forgive Trump for telling Scouts that Washington is a “sewer.” Actually, that message could be an antidote to much of what Scouts hear. Trump’s speech, insofar as it spurs doubts about political authority, could be far more salutary than prior presidential Jamboree speeches.

When I attended the 1969 Scout Jamboree in Idaho, President Richard Nixon sent us a message praising our idealism. But the type of idealism that Nixon and the Scouts often glorified was more likely to produce servility than liberty. Before being accepted into the Jamboree troop, I was interviewed by adult Scout leaders in a nearby town. The most memorable question was: “What do you think of the Vietnam situation?” Even 12-year-olds had to be screened for dissident tendencies.

The Idaho Jamboree occurred one month before the Woodstock music festival. Instead of tens of thousands of people chanting antiwar slogans, the Jamboree exalted the military in all its forms. Instead of acres of half-naked hippies, the Scouts were protected by “uniform police” who assured that every boy wore a proper neckerchief at all times. Instead of Joan Baez belting out “We Shall Overcome,” the Scouts listened to “Up with People,” a 125-member singing group created as an antidote to “student unrest and complaining about America.”

The motto for the 1969 Jamboree was “Building to Serve.” But I later wondered: Building to Serve whom? The Jamboree put one government official after another on a pedestal, starting with Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare Peter Finch — and extending to anyone with a three-word government title. Letting politicians define the goals and terms converted service into a recipe for servitude.

After the Idaho trip, I lingered in the Scouts long enough to finish the requirements for Eagle rank. The official Eagle Scout pocket card I received included Nixon’s signature as “honorary president” of the Boy Scouts of America. The Scouts presented Nixon with their highest civilian award — the Silver Buffalo — about the same time his aides commenced clandestine operations that would make Watergate a household name.

Scouting has helped toughen millions of boys. But, at the same time, Scouting has too often encouraged unquestioning deference towards authority. Scouts have perennially been used as props to create an impression of popularity and rectitude for politicians.

When President Lyndon Johnson addressed a Scout Jamboree in 1964, he declared that seeing the Scouts’ “smiling, optimistic faces . . . will give me strength that I need in the lonely hours that I spend in attempting to lead this great nation.” Johnson also told the boys that “government is not to be feared.” But Johnson’s Jamboree appearance did not dissuade him from sending half a million troops to Vietnam, where some of the boys who heard his uplifting spiel that day likely pointlessly perished in a war for which LBJ continually deceived the American public.

First Lady Nancy Reagan addressed the Jamboree in 1985 (her husband was recovering from surgery), and told the boys that “No one can use drugs and remain a true Boy Scout . . . Scouts can help save their generation from drugs.” The war on drugs that the Reagans re-ignited helped turn inner cities into war zones and sent millions of Americans to jail and prison. Almost everyone exceptAttorney General Jeff Sessions now recognizes that folly.

President Bill Clinton addressed the 1997 Jamboree and gushed about the need for doing “good turns” and service — safe pablum for a president who had been hounded by scandals and independent prosecutors for four years (he was impeached the following year). Clinton closed with Washington’s favorite bogus de Tocqueville quote — “America is great because America is good” — the type of feel-good pablum forever cheered by slacker pundits.

President George W. Bush used his 2005 Jamboree speech to recycle War on Terror rhetoric: “You’ll find that confronting injustice and evil requires a vision of goodness and truth… All of you are showing your gratitude for the blessings of freedom.” But the Bush administration had long since demolished constitutional protections for privacy and was secretly championing torture as a key to the victory of good over evil.

In the controversy after Trump’s speech, some on the Left have compared the Boy Scouts to the Hitler Youth. But it is unfair to the young folks who heard Trump’s spiel to presume they will become mindless Trump-bots — or even Republicans — in perpetuity. Instead, Trump’s bombast may have helped turn some of the attendees into lifelong skeptics of any politician on the hustings — a welcome corrective to Scouts’ endless pledges of obedience.

James Bovard, author of Public Policy Hooligan, is a member of USA TODAY’s Board of Contributors. Follow him on Twitter @JimBovard

xxxxxxxxx

USA TODAY, May 12, 2015

Boy Scouts should stay tough, not pander to gender gap

by James Bovard

Scout leadership is turning Boy Scouts into kale — nutritious, but blech

The Boy Scouts are once again reforming themselves into oblivion. With falling enrollment nationwide, the Scouts are desperate for good publicity. Their latest politically correct gambit involves offering STEM programs for boys and including girls to help close the “gender gap.”

The Boy Scouts are launching STEM Scouts to focus on “the frontiers of science, technology, engineering and math.” After conducting market research that supposedly proved that a “values-based STEM program” would rev up boys and their parents, STEM Scouts are debuting in a dozen Scout councils across the nation this Fall, with further expansion pending.

Are the Boy Scouts behaving like a federal agency – adding a new mission statement goal in lieu of fulfilling their traditional purpose? More than 220 different federal programs now promote STEM education and schools across the nation are pounding the STEM pulpit with religious fervor. Though there is no shortage of STEM efforts, the Boy Scouts have jumped on this bandwagon.

The Scouts, like plenty of government agencies, may be promising far more than they can deliver on STEM. My father was a scoutmaster, and with his Ph.D. in animal genetics from Iowa State, helped spur several troop members to pursue higher education. But it is rare to find a Scout leader equally comfortable with calculus and a compass. Most of the locales for STEM Scouts are in areas with well-known universities. The talent pool for adult leaders for such programs will be far thinner in most of rural America.

The most radical innovation in the new STEM program is to bring in girls to a Boy Scout program in order to close the “gender gap.” Boy Scout chief executive officer Wayne Brock declared that the Scouts “hope to be part of the solution to the disparity between the genders in their representation in STEM fields,” bringing “into better balance” the number of male and female engineers and computer and math professionals.

Should parents of boys in scouts worry that staff and resources will be diverted from traditional Boy Scout programs and into an affirmative action programs for girls? The Girl Scouts aren’t proposing a new program to enlist boys to close their “knitting, baking, and empathy gap,” so why should Boy Scouts worry about the STEM gap?

Besides, the Girl Scouts already have plenty of robust STEM programs around the nation. Two Ohio Girl Scout troops recently attended a manufacturing and STEM workshop at the Scarlet Oaks Career Campus of Cincinnati. In March, the Girl Scouts of Eastern Massachusetts held an annual STEM conference and Expo in Framingham, Mass. In December, 300 Girl Scouts participated in the “Cyber Pathways for Middle School Girls” event at Cal State San Bernardino. A West Virginia Girl Scouts council is carrying out a “Imagine Your STEM Future” program.

And the Boy Scouts also have ample STEM programs up and rolling. Scouts can earn merit badges for several STEM-related fields, including robotics. The Scouts launched a national STEM initiative in 2011 that seemed to be doing just fine. Eight hundred scouts attended the National Eagle Scout Association’s STEM Jamboree at the Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland last year. Last September, a Boy Scout council ran a program for Oklahoma boys to build and launch free model rockets – great fun though this particular expertise may cause Homeland Security and Secret Service agents to sweat.

The skills I most enjoyed learning in the Scouts – building fires, camping in winter, shooting white water rapids in a canoe – involved getting your hands dirty and surviving bumps and bruises. While attending a National Scout Jamboree in Idaho, I also learned how much I dislike marching in step with thousands of other people. Scouting taught me to view minor hardships simply as transaction costs for great adventures.

The Scouts are ill-advised to shift away from their rough-and-tumble heritage. The people who hate the Scouts will not be mollified by the latest STEM gambit, and some kids who might have joined will be put off by expectations of another dreary science class.

“Join the Boy Scouts to help girls close the Gender Gap!” is not the snappiest recruiting slogan yet devised. Is the Scout leadership turning Boy Scouts into the equivalent of kale — something reputedly very nutritious that many people will not stomach?

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

Future of Freedom Foundation, July 2016

Boy Scouts and the Love of Freedom

by

July 1, 2016

Some of my anarcho-libertarian tendencies arose thanks to the years I spent as a Boy Scout. Joining the Scouts was an easy decision, since my father was a Scoutmaster. Even without the family obligation, I might have signed up because Troop 52, based in Front Royal, Virginia, took many exhilarating excursions. My father had a knack for convincing boys that they were having fun even in the bitter cold or driving rain.

Troop 52 often hiked along the nearby Appalachian Trail. On one jaunt, we camped overnight on a mountain ridge about 20 miles south of Front Royal. Along with two other boys, I was roaming after dinner when we spotted a big black bear foraging the outskirts of the campground. I have forgotten who threw the first rock at the bear, but strong circumstantial evidence suggests it was I. The one certainty was that, once that bear charged at us, I was the fastest runner. Back then, it was rare for Virginia black bears to maul people. In this case, the bear reacted like a horse swishing its tail to brush away flies. After putting us to flight, it resumed scavenging.

Along with other Scouts, I sometimes hiked five miles cross-country from the first crest in the Shenandoah National Park to the Beef Cattle Research Station, where I lived. We did not realize that the ruins of old cabins we encountered were vestiges of a brutal public-works project that entailed the forcible eviction of people from their homes. In the 1930s, politicians confiscated 176,000 acres of private land to create a huge park intended to serve as a playground for presidents. Mountaineer families were paid as little as one-tenth the value of their land and falsely vilified as lazy, good-for-nothing parasites. When some owners refused to budge, they were forcibly dragged from their cabins and their homes were burnt down to ensure they never returned. The sordid details of the park’s creation vanished from local memories, and I did not learn of the plundering until long after I left my hometown.

Jamboree

My most formative Scouting experience involved a trek to the Northwest for the 1969 National Jamboree. Each of the nation’s 300 Boy Scout Councils sent one troop selected from members of all the troops in that council. I applied to join the troop from the Shenandoah Area Council, which comprised the northern Shenandoah Valley and a chunk of West Virginia. When I was interviewed in December 1968 at Council headquarters in Winchester, Virginia, the most memorable question was, “What do you think of the Vietnam situation?” Even 12-year-olds had to be screened for dissident tendencies.

The 45 members of the Shenandoah Area Council Jamboree troop met at Camp Rock Enon, on the Virginia–West Virginia border, for two weekend training sessions before heading west. I was dumbfounded when we spent three hours marching back and forth on a drill field. That time could have been far better spent climbing trees or setting brush fires. There was far more regimentation in this select group than I had experienced in my hometown troop.

Some of the kids in the Shenandoah Area Council Jamboree troop were natural-born bootlickers who probably went on to become personal-injury lawyers, zoning commissioners, or maybe USDA meat inspectors. On the trip to and from Idaho, we often stayed at military bases. I was thrilled at 17-cent breakfasts with unlimited servings. I did not realize that the vittles were so cheap in part because the guys serving us were conscripts whose labor cost the government almost nothing.

In South Dakota, I was far more impressed by the Badlands than by Mount Rushmore. Like most Scouts, I subscribed to the Patriotic Version of American History. After visiting the Little Big Horn Battlefield National Monument, I jotted that the Seventh Cavalry’s “heroic defense made the nation yearn for details that no white man lived to tell.” Many years later, I learned that Custer’s men were wiped out in part because the Army quartermaster refused to permit them to carry repeating rifles — which supposedly wasted ammunition. The Indians didn’t have a quartermaster, so they had repeating rifles, and the rest is history.

The Jamboree was held at a state park near Coeur d’Alene in the rugged mountains of northern Idaho. Even in mid July, the ground seemed frozen when I hammered in tent pegs. The biggest surprise was that the water for showers was piped in directly from the Arctic Ocean — or so it felt. But those were minor aggravations quickly forgotten in the thrill of swapping stories and patches with guys from around the nation.

On the Jamboree’s first evening, all the attendees marched into a massive arena for opening ceremonies. I found myself immersed in the biggest herd I ever encountered — 35,000 people, all dutifully striding in the same direction. Being pulled into that vortex literally made me gasp for breath.

Each troop at the Jamboree presented historical or cultural skits from their area. My troop relied on hillbilly humor and ballads — offerings which left me cold. The troop’s musical presentation had nothing of the robust bluegrass spirit of Bill Monroe or Flatt and Scruggs.

The Idaho Jamboree occurred one month before the Woodstock music festival. Instead of tens of thousands of people chanting antiwar slogans, the Scouts roared when they heard Richard Nixon’s message hailing their idealism. Instead of acres of half-naked hippies, the Scouts were protected by “uniform police” who ensured that every boy wore a proper neckerchief at all times. Instead of Joan Baez belting out “We Shall Overcome,” the Scouts listened to Up with People, a 125-member singing group created as an antidote to “student unrest and complaining about America.”

When the time for the final night’s grandiose assembly arrived, I could not tolerate another mass march. I forged a press pass and entered the amphitheater early to get near the main stage to take pictures. The photos came out lame but it was small price to avoid re-immolation in a multitude.

That final ceremony included a presentation by the camp chief on the seven-point statement of commitment to help attendees carry the lessons learned into their lives after they returned home. One of the points warned against the “weakening of youth’s self-respect by the increasing use of drugs, tobacco, and alcohol.” Perhaps inspired by that admonition, I did not start smoking cigars until I turned 15.

Lessons

The Shenandoah Area Council troop remained at the site one day after the Jamboree formally ended. On my final evening in Idaho, I took off alone rambling over the vast, nearly-empty tract — cherishing the lush mountains, the sky-high pine trees, and a few precious uncrowded hours. That trip definitely taught me to better appreciate solitude.

While the Jamboree celebrated authority and obedience, a different theme emerged some miles to the north 23 years later. “Ruby Ridge” became notorious after U.S. marshals killed 14-year-old Sammy Weaver and an FBI sniper slew Vicki Weaver as she stood in her cabin door holding her baby. Federal prosecutors insisted that Randy Weaver’s family’s move from Iowa to Ruby Ridge proved they were conspiring to have an armed confrontation with the government. Actually, moving to northern Idaho was more akin to relocating to Mars. The wrongful killings and lies that permeated that case convinced millions of Americans that Washington was profoundly untrustworthy. My writings on the case were denounced by FBI Director Louis Freeh: “Mr. Bovard insults the courageous men and women agents of the FBI when he suggests that they would ‘wantonly shoot private citizens based on mere suspicion.’”

After the Idaho trip, I lingered in the Scouts long enough to finish the requirements for Eagle rank. The official Eagle Scout pocket card included Nixon’s signature as “honorary president” of the Boy Scouts of America. I should have kept that card with me to display during frequent encounters with the police in the following years. The Scouts presented Nixon with their highest civilian award — the Silver Buffalo — at the same time his aides commenced clandestine operations that would soon make “Watergate” a household word.

The Scouts were in favor of freedom as a traditional American value — just as long as no one stirred up any trouble. Every Boy Scout meeting opened with a pledge to “do my duty to God and country.” But the more obedience I vowed, the more dubious I became.

The motto for the 1969 Jamboree, for instance, was “Building to Serve.” But I later wondered: Building to Serve whom? The Jamboree put one government official after another on a pedestal, starting with Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare Peter Finch and extending to anyone with a 3+ word title. Letting politicians define the goals and terms converted service into a recipe for servitude.

I became leery of the Scouts’ endless paeans to leadership. Supposedly, if we all rallied around the leader, everything would always work out fine. “Leadership” often meant simply a knack for herding other people in the direction authorities approved. The prouder of being leaders Scouts were, the more willingly they sacrificed themselves for their superiors. How many boys who attended the Jamboree later pointlessly died in Vietnam? They perished as martyrs to political frauds — in part because of the Scout doctrines they imbibed.

Scouting also made me wary of tub-thumping benevolence. The more good deeds people supposedly performed, the more deluded they sometimes become. And the resulting “moral body count” often was as dubious as the government-program success statistics that I began debunking as a journalist a dozen years later.

On the cheerier side, Scouting made me more of an outdoorsman and accustomed me to ignoring paltry pains — i.e., aches that were not completely debilitating. When I spent a summer hitchhiking around Europe in 1977, I used the same plastic tarp and sleeping bag that served me well with the Scouts on the Appalachian Trail. The European jaunt required constant juggling and jerry-rigging, from sleeping by the side of the road and waking up raring to go, to limping away from an 18-wheel truck crash that obliterated the mini-car I was riding in. Thanks to Scouting, I learned to see minor hardships simply as transaction costs for great adventures. And that Idaho trip vivified that the playing field of life was far bigger than Front Royal — or even Virginia.

This article was originally published in the July 2016 edition of Future of Freedom.

Comments are closed.